120 Images Rarely Seen In History Books

The past can be quite fascinating. Those of us living in the present find it really interesting what life was like 50, 100, or even a 1,000 years ago. Luckily, we can go almost 200 years to the past thanks to photography, as the oldest surviving photograph is from 1826.

It’s even more interesting when old historical photos teach us something new. That’s the mission of the Undiscovered History Facebook page. It’s a popular account with over 540k followers that teaches its fans a bit of everything: history, aesthetics, and even interesting facts. So scroll down and explore history through the medium of pictures!

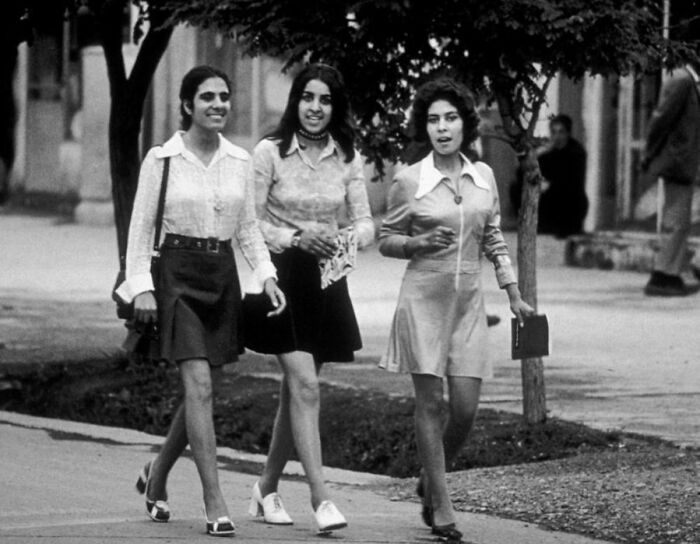

#1 Three Female Students Walk In The City Of Kabul, Afghanistan, 1972

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#2 A Portrait Of Hollow Horn Bear, A Man From The Brulé Native American Tribe. 1907

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#3 A Mother And Her Eight Sons, All Served, All Came Home

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

Undiscovered History is one of the few online accounts run by the folks at History Defined. It’s a blog that shares important and unusual historic facts and stories we probably don’t learn in a history class at school. Their content includes such interesting stories as why Christian monks had such weird haircuts and the fashion of the decades from the 1920s up to the 1990s.

Besides this Facebook page, you can find History Defined and their content on Instagram, X, and YouTube. We’ve actually covered their IG page a couple of times, and you can find the article here and here. Their X page is currently the most popular with over 670k followers.

#4 Blackfoot Tribe In Glacier National Park, 1913

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#5 Cats Wait For The Fisherman To Return, Istanbul, 1970s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#6 A New York Policeman Hanging From A Girder, 1920

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

The content channel describes their goal as “to create exciting content, whether you’re casually interested in history or an expert.” The Instagram page came first in October of 2021, and other social media accounts followed. They also accept contributions from their followers, asking them to reach out through their contact page.

In May 2023, History Defined launched the Threads of History Facebook group, taking their audience’s submissions even further. That’s where their followers and fans can share any fascinating stories and photos from the past they find interesting and worth sharing.

#7 A Man Posing With A Donkey In His Lap, 1910s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#8 Idaho Winter, As Experienced In 1952

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#9 A Four-Year-Old Child Helping Her Family Pick/Dig Potatoes, 1931

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

Nowadays, we consume tons of visual media. Videos, photos, cinema, and TV can help us learn new things every day. However, they can just as easily misinform us. With the rise of AI-generated images and other means to doctor photographs, it’s hard to know when we can trust what we see as true. Interestingly, what we now consider historical images were sometimes altered even before the advent of Photoshop.

#10 A Kid’s Reaction To Meeting Andre The Giant (1970’s)

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

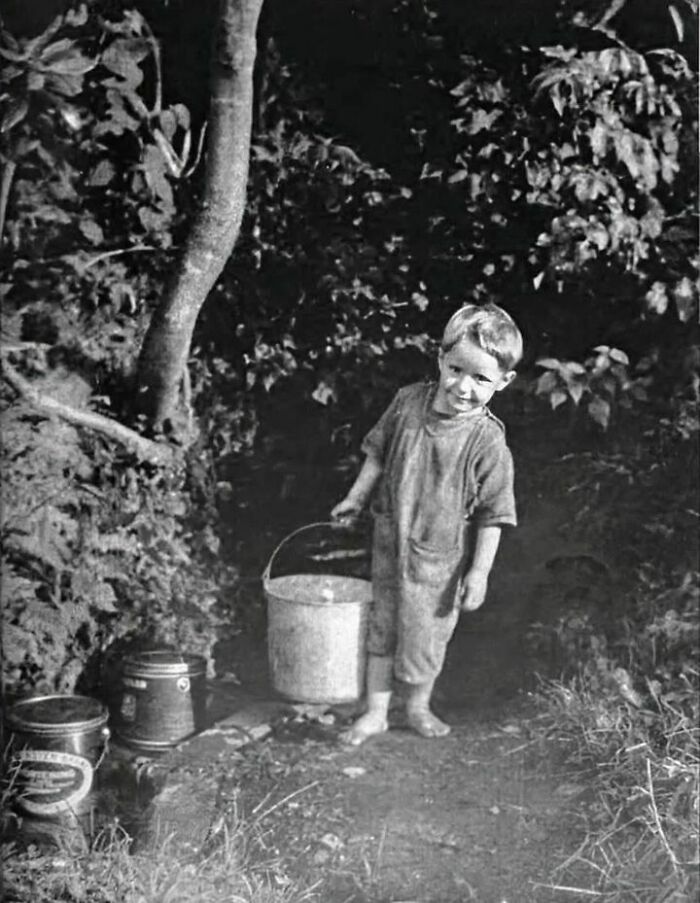

#11 A Mountain Boy Fetches Water From A Spring, Great Smoky Mountains, Sevier County, Tennessee, Ca. 1950

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#12 A Young Boy And His Dog From 1889

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

Perhaps the most iconic portrait of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln is actually fake. In the image, Lincoln is standing, but that’s not his body. Printmakers superimposed his head from a 1964 portrait by Anthony Berger onto John Calhoun’s body. Hany Farid, a professor specializing in image analysis at Berkeley University, claims it might’ve been because there were no “heroic style” portraits of Lincolns at the time.

#13 Jim Carrey, Christmas 1967

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#14 Federico Caprilli Demonstrates The Skills Of His Horse As Part Of The Esteemed Italian Cavalry School, 1906

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#15 4 Generations In 1 Picture, 1880s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

Stalin was a big fan of removing his enemies and those who fell out of his favor from photographs. One example is a 1922 image where the dictator is standing next to the Moscow canal. In the original photo, a secret police official Nikolai Yezhov is standing next to him. But in 1938, he fell out of Stalin’s favor and was secretly arrested, tried, and executed. Thus, the leader had photo retouchers remove him.

#16 A Photograph Of A Little Boy Carrying A Newborn Lamb, In Scotland, 1932

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

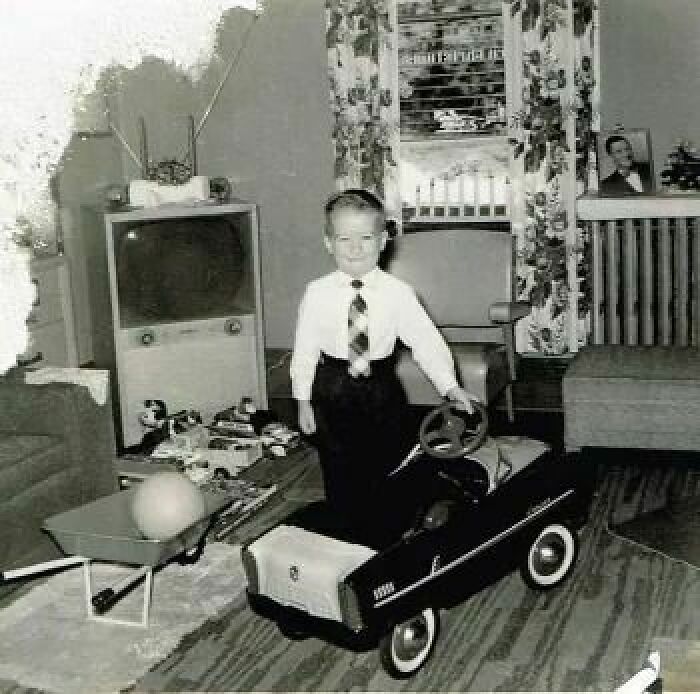

#17 A Little Boy All Dressed Up Standing By His New Pedal Car. 1958

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#18 Just Divorced, 1930s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

The National Geographic is also a culprit when it comes to altering images. Their February issue cover in 1982 featured the pyramids of Giza. However, in the image they used, the two pyramids are too close together than they are in reality.

The magazine later expressed their regrets and said: “We no longer use that technology to manipulate elements in a photo simply to achieve a more compelling graphic effect. We regarded that afterwards as a mistake, and we wouldn’t repeat that mistake today.”

#19 Three Lacemakers Working. Brittany, France. 1920

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#20 Monet With His Wife Alice, 1908

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#21 The Shape Of The Statue Of Liberty Is Formed By 18,000 Soldiers Standing In Formation. Camp Dodge, Des Moines, Iowa, USA. Ca. 1918

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

Did you know the iconic album cover for The Beatles’ Abbey Road was also altered? In the original, Paul McCartney was holding a cigarette in his right hand. In the United States, the poster companies airbrushed the images and removed the cigarette from his hand in 2001, 14 months after George Harrison passed away from cancer.

Apple Records later issued a statement, saying they never agreed to this. “It seems these poster companies got a little carried away. They shouldn’t have done what they have, but there isn’t much we can do about it now.”

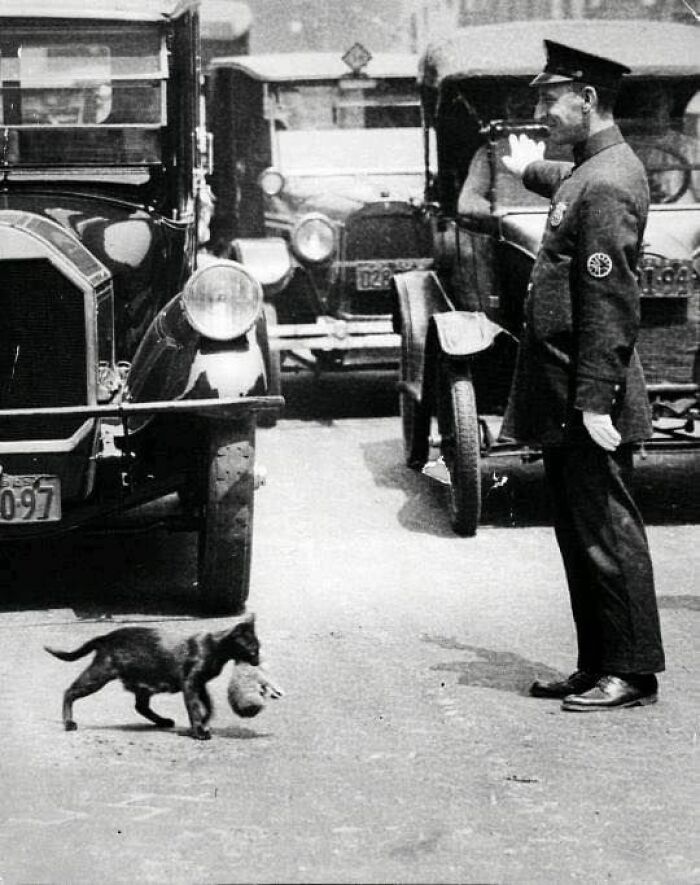

#22 An Officer Halts Traffic To Make Way For A Cat Carrying A Kitten Across The Street, 1925

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#23 King George Vi Bursting With Excitement On A Theme Park Ride – 1930s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#24 3 Sets Of Twin Girls Pose Together For A Portrait In 1895

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

A 1970 photograph by photojournalism student John Filo taken at a protest against the war in Vietnam was doctored as well. But not in an attempt to change history. The original simply broke the main aesthetic rule of photography: a fence post terminated on top of the subject’s head. The photograph won a Pulitzer prize, so, it was worth it, probably?

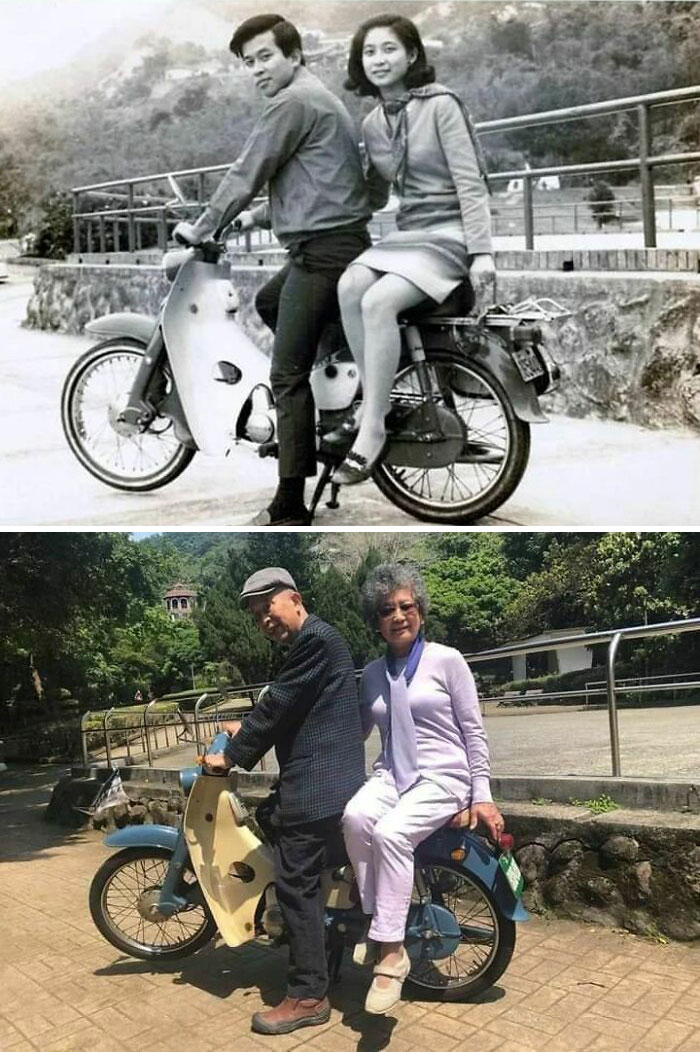

#25 1967-2018 Same Bike, Same Couple

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#26 Photo Of Lumberjacks Cutting Trees In Pacific Northwest, USA 1915

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#27 A Boy Selling Lemonade With A Portable Lemonade Dispenser. Berlin, 1931

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

And how can we forget to mention celebrities getting airbrushed on the covers of magazines? One of the earliest examples was a TV Guide cover of Oprah. The editors superimposed her head on the ’60s star Ann-Margaret’s body. Interestingly, the magazine didn’t ask either woman’s permission before they chose to do that.

#28 New York City Ca.1940

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#29 Lockheed Martin Employee Sally Wadsworth Working On The Fuselage Of A P-38 Lightning In California, 1944

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#30 An Empire State Builder Hanging On A Crane Above New York City, 1930

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

Photographs can be a great source of history. But, sometimes, we should take them with a healthy dose of skepticism. As David Levi Strauss writes for TIME magazine, “Technical images have now become a form of information, to be consumed like all other bits and bytes. As we consume them, we should perhaps take a moment to reflect, not just on how we manipulate and change them, but also on how we are manipulated and changed by them.”

#31 1969 And 1970’s Cars For Well Below $3000

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

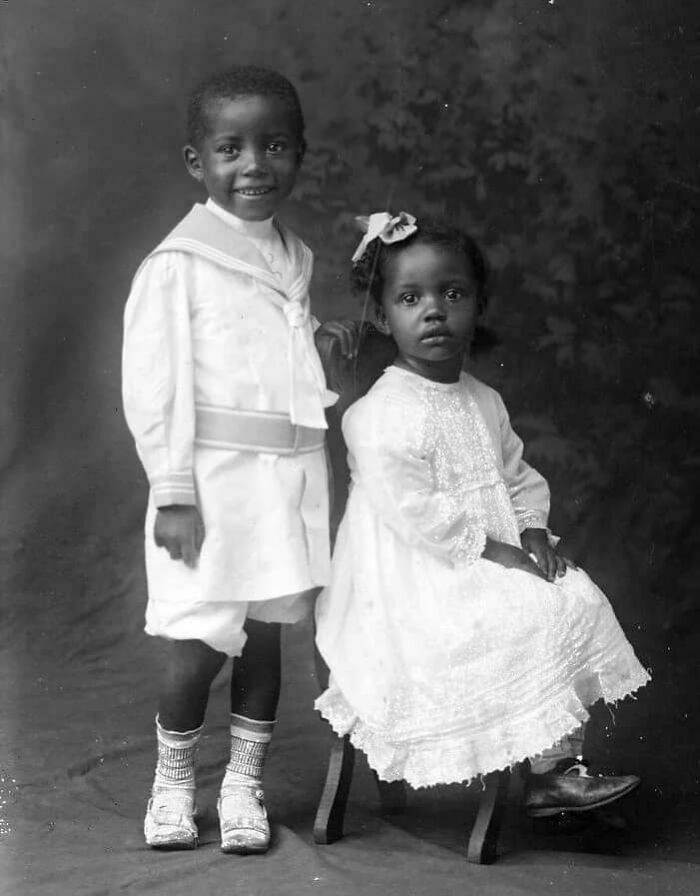

#32 A Sweet Photo Of A Brother And Sister. Charlottesville, Va, C. 1916

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#33 A Lovely Photo Of A Brother And Sister. I Love Their Fashions And Her Purse! Chicago,. 1945

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#34 Old-Time Appalachian Musicians With A Pooch On The Porch

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#35 Charlie Chaplin Meeting Helen Keller, 1919

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#36 Looking Out The Window Of Apollo 11, July 1969

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#37 Seiko TV Watch From 1982

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#38 A Man On The Porch Of His Cabin, Eagle Creek, Murray, Idaho, 1889

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#39 A Stylish 1940s Group Portrait

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#40 A Taco Bell Menu From 1972

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#41 The Cast Of Alice, 1979

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#42 The Traveling Wilburys, 1980s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#43 3 Beautiful Children From The 1900s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#44 An Old-School KFC Menu

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#45 Mcdonald’s Parties In The 80s Were Epic!

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#46 Wooden Railway Bridge. USA, Montana, 1883

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#47 Portrait Of A Mother And Her Daughter. Photographed In 1910

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#48 Kids Cheering On The Way Out The Door On The Last Day Of School, 1977

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

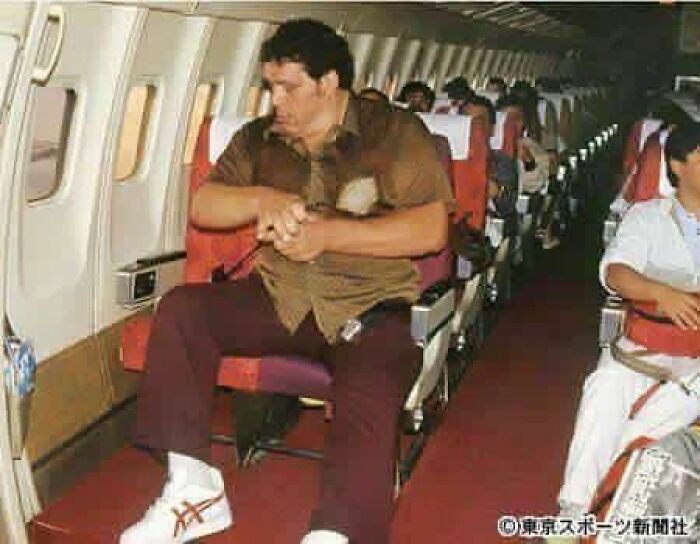

#49 Andre The Giant Flying Out Of Japan, 1980

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#50 3 Beautiful Children From 1901. Hattie, Clarence, And James Harold Ward

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#51 A Woman Churning Milk To Butter While Reading A Book, 1897

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#52 A Lady From High Society. Ottoman Empire, 1900s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

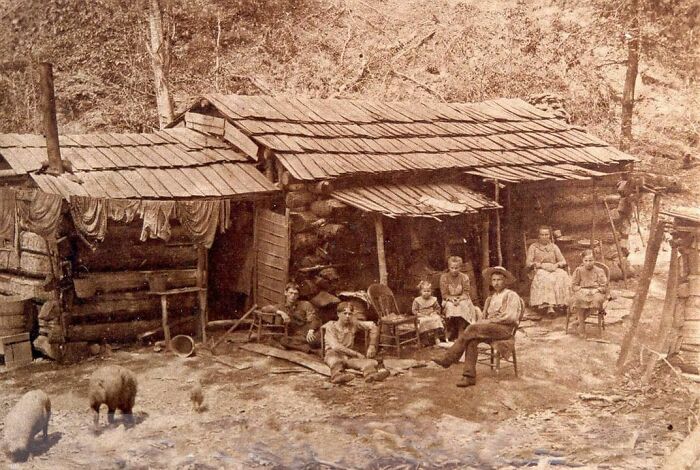

#53 A Family At Their Cabin Home In West Virginia, 1900

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#54 Unbelievably Stunning Couple (Love How Their Hands Are Clasped Together), 1960s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

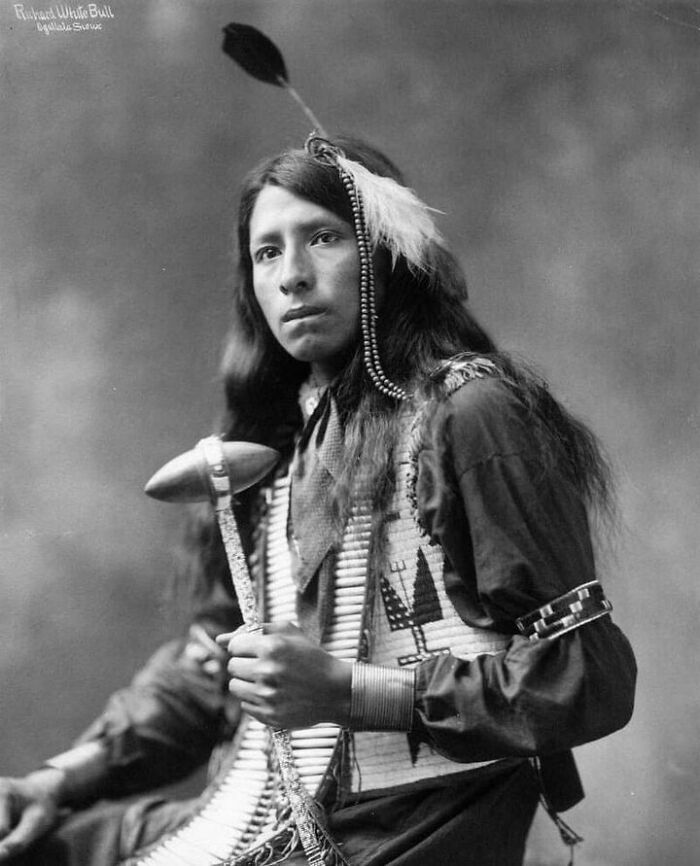

#55 Richard White Bull, Oglala Sioux, 1899

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#56 Female Swimmer Posing On The Beach. Deauville, France. Ca. 1925

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#57 London Pub, 1967

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#58 In 1960, David Latimer Planted A Spiderwort Sprout Inside Of A Large Glass Bottle, Added A Quarter Pint Of Water, And Then Sealed It Shut

He opened the bottle 12 years later in 1972 to add some water and then sealed it for good. The self contained ecosystem has flourished for more than 60 years. For those who are wondering how this is even possible: the garden is a perfectly balanced and self-sufficient ecosystem. The bacteria in the compost eats the dead plants and breaks down the oxygen that is released by the plants, turning it into carbon dioxide, which is needed for photosynthesis. The bottle is essentially a microcosm of earth.

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#59 A Cool Girl Posing With Her Car Around 1920

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#60 Three Young Boys Sit In A Wagon In A Pittsburgh Neighborhood Street, 1920-1930

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#61 Kids Playing, New York, 1940s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

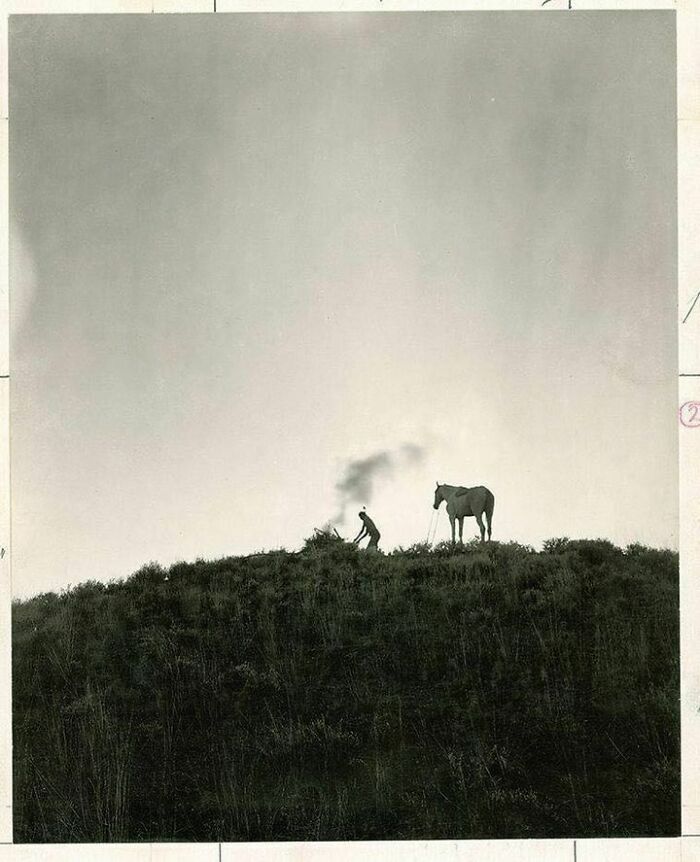

#62 A Native American Sends Smoke Signals In Montana, June 1909

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#63 Tricycle From 1936

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#64 People Gathered In Front Of Stores In A Small Town. Eureka Springs, Arkansas, 1880

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

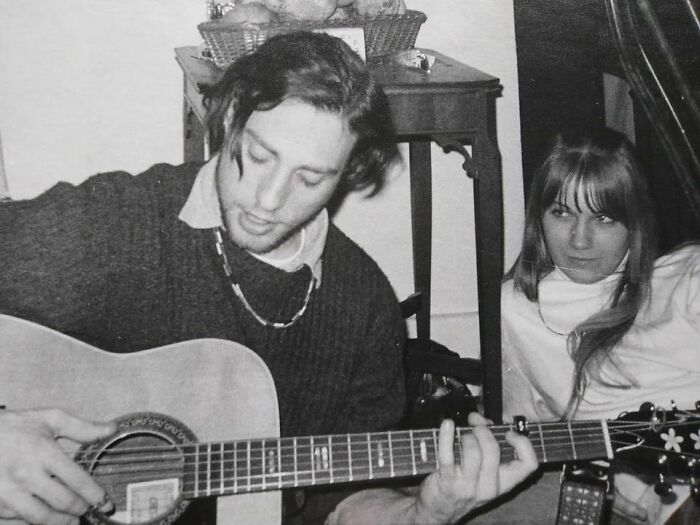

#65 Grandparents The Night They Met (1970)

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#66 Rolling To Work, 1940’s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

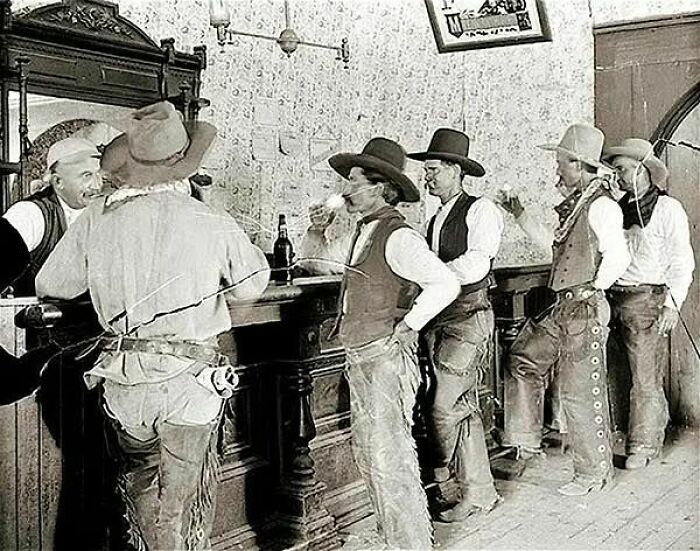

#67 Cowboys Enjoy Drinks At The Equity Bar In Old Tascosa, Texas, 1907

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#68 Children In The Slums Of Cumberland Street. Dublin, Ireland, 1940

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

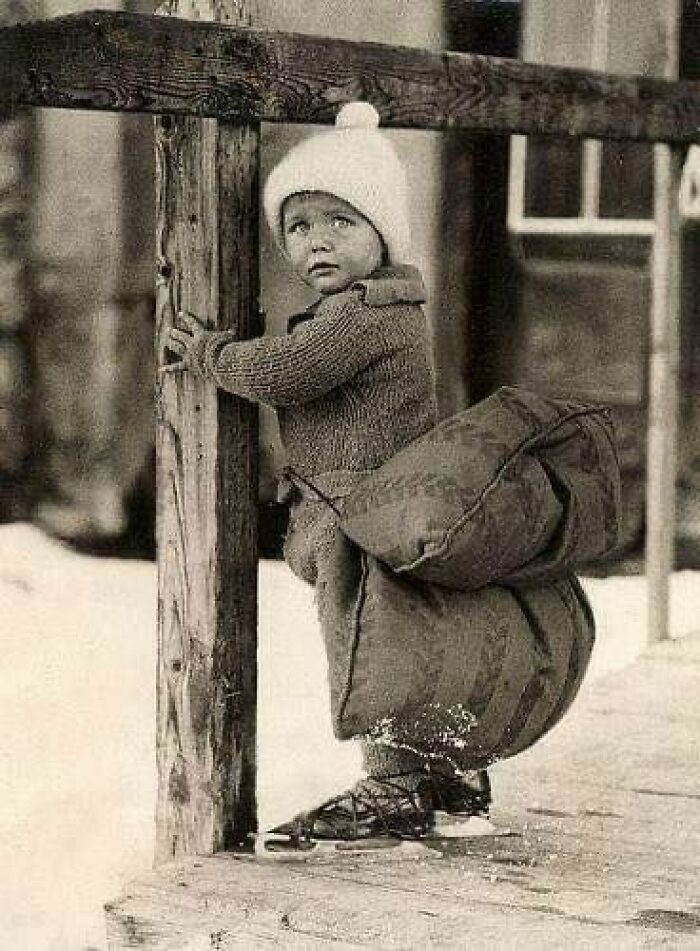

#69 Dutch Boy With A Pillow Strapped On His Backside To Soften The Falling On Ice While Skating, 1933

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#70 Lady And Her Horse On A Snowy Day In 1899

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#71 Marlene Dietrich Kissing A Soldier Returning From Wwii, 1945

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#72 A Female Firefighting Team On A Converted Motorcycle In London, 1932

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

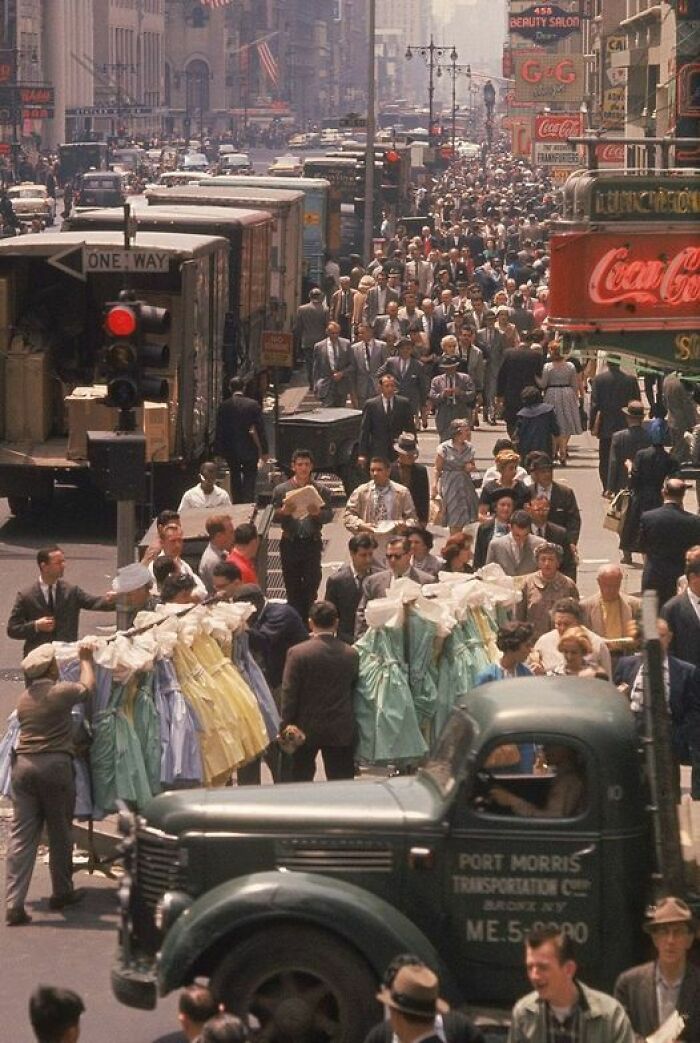

#73 New York City Around 1960

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#74 Young, Well-Dressed, Victorian Girl In 1902

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#75 Woman Packinghouse Worker From Tennessee With Three Of Her Four Children Eating Supper Of Fried Potatoes And Cornbread And Canned Milk. Belle Glade, Florida

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#76 The Family Of A Migratory Fruit Worker From Tennessee Now Camped In A Field Near The Packinghouse At Winter Haven, Florida, 1937

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#77 The Opening Of The Eiffel Tower During The 1889 World’s Fair

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#78 New York City 1960

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#79 70s Fashion

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

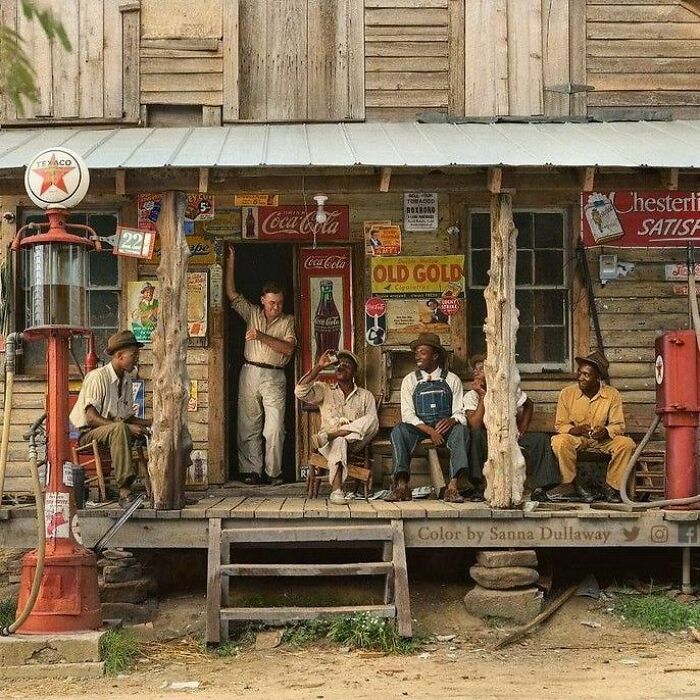

#80 Country Store On A Dirt Road, North Carolina In 1939

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#81 Ruth Disney Seen Standing With Her Big Brother Walt (1906)

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

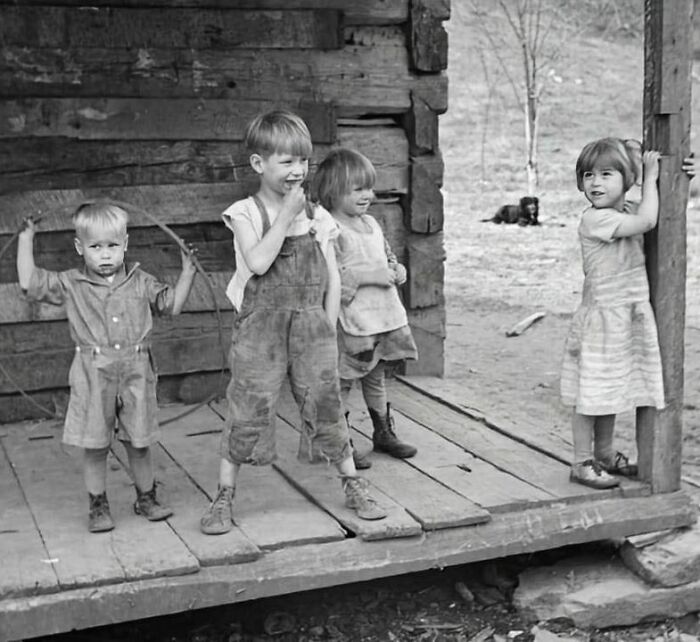

#82 A Little Gang From Ohio, 1936

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#83 McDonald’s Menu In 1960

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

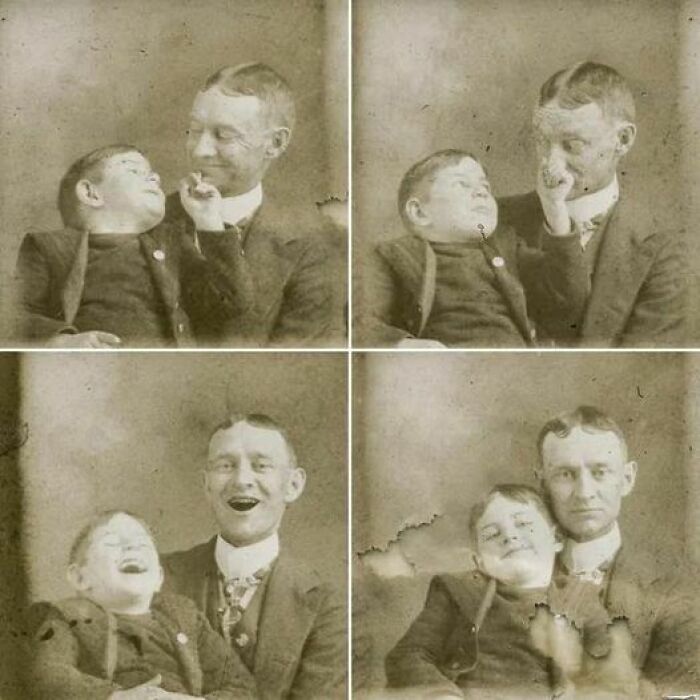

#84 Father And Son Take Silly Photos, 1910s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#85 Family In Front Of Shack Home, Mays Avenue Camp. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#86 Residents Of West Berlin Show Their Children To Their Grandparents Living In East Berlin, 1961

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

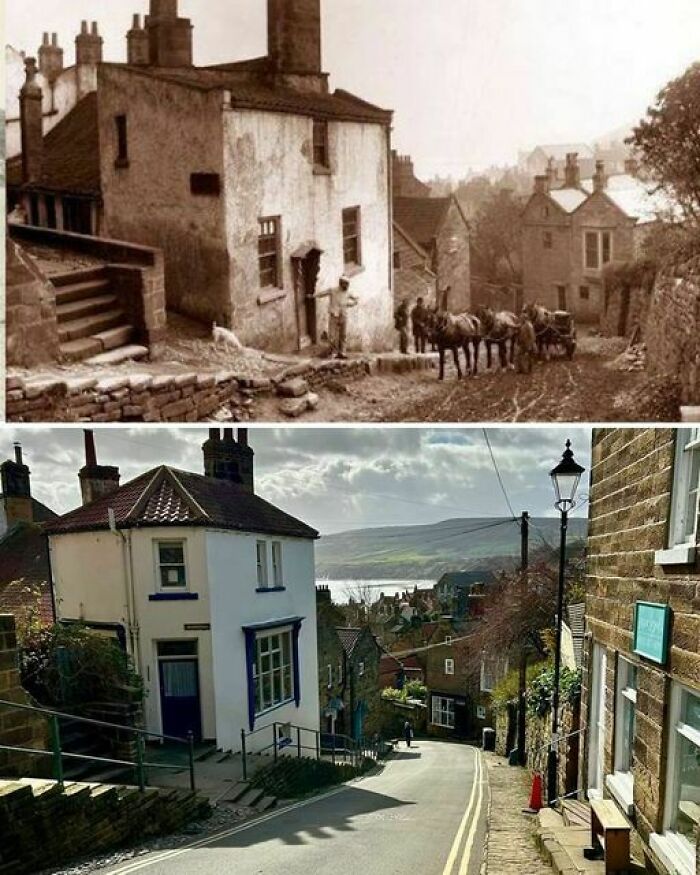

#87 Stunning Then And Now Comparison Of Robin Hood’s Bay, A Picturesque Old Fishing Village In Yorkshire

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

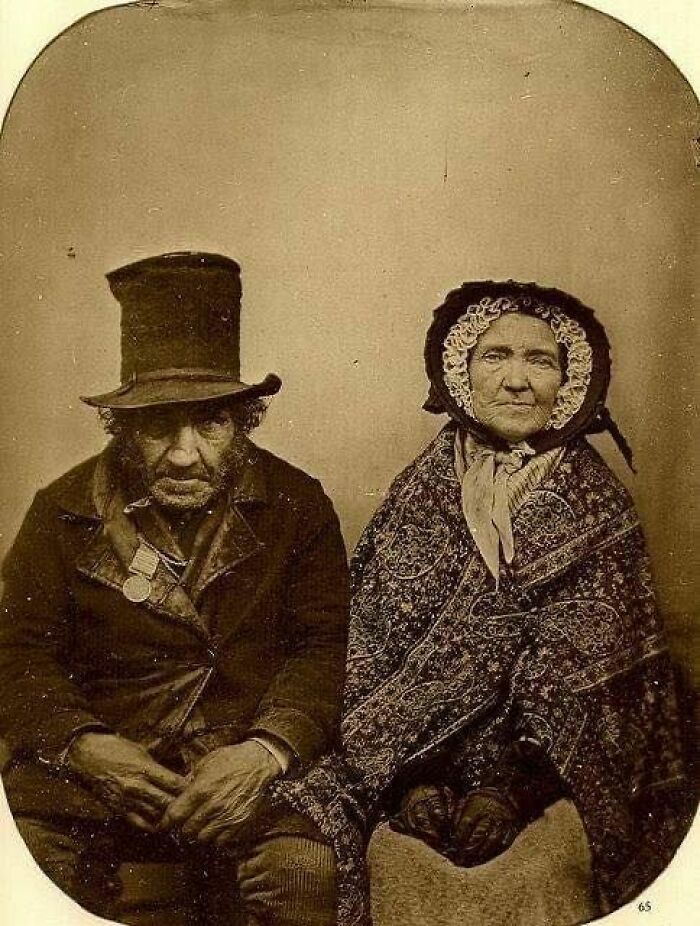

#88 Photograph Of An Elderly Man And Woman Wearing Work Clothes And Seated On A Pile Of Firewood

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#89 Former Sharecroppers, Just Before Moving To Southeast Missouri Farms. 1938

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#90 Two Young Women Walking Along Broadway Between 48th And 49th Streets. New York (1969) What Stands Out?

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#91 Young Woman Removing Her Loaf Of Bread From The Oven, 1909

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#92 Boy Selling Coca Cola From A Roadside Stand, 1936

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#93 American Woman Welders During World War II

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#94 Barefoot Kids At A Mobile Book Cart In The Appalachian Mountains

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#95 The Old Cincinnati Library Before Being Demolished, 1874-1955

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#96 Young Riders Refuel During A Children’s Sidecar Race In The Lustgarten In Berlin, Germany (1931)

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#97 Rural Mail Delivery In 1914

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#98 Two Gentlemen From The Early 1900s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#99 In The Kitchen Of A Montana Farmhouse, 1900

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#100 Portrait Of A Boy On A Rocking Horse, 1902

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#101 Southern Ohio Family In Front Of New Washing Machine, 1911

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#102 Cyclist From Estonia, On A Self-Made Bicycle, 1912

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#103 Ozark Mountain Family At Their Cabin In Arkansas

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#104 A School In Seattle 144 Years Ago!

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#105 Even The Window Cleaners Wore Suits 100 Years Ago

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#106 A Couple From 1850!

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#107 Going To Mcdonald’s In The 1950s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#108 The Comfortable Living Room (1930)

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#109 Mother With Her Daughter In 1880

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#110 A Family Living In London’s Slums, 1900s

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#111 This Photo From 1902 Shows French Knife Grinders. They Would Work On Their Stomachs In Order To Save Their Backs From Being Hunched All Day. (France 1902)

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#112 These Progressive High School Girls Learn The Finer Points Of Auto Mechanics In 1927

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#113 Irish Fishermen, Ireland 1910

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

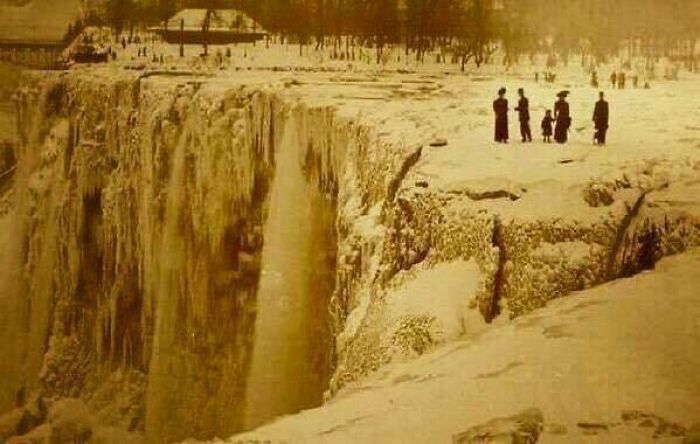

#114 Rare Photo Showing Niagara Falls Completely Frozen Over In The Year 1911

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#115 Acrobats Balance On Top Of The Empire State Building, 1934

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#116 A Group Portrait Taken At A Wedding In Norway, 1900

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#117 Milkman Dropping Off And Picking Up Milk, 1939

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#118 Trappers And Hunters In The Four Peaks Country In Brown’s Basin, Arizona

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

#119 A Woman Using A Spinning Wheel Outside Of Her Log Cabin, 1918

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

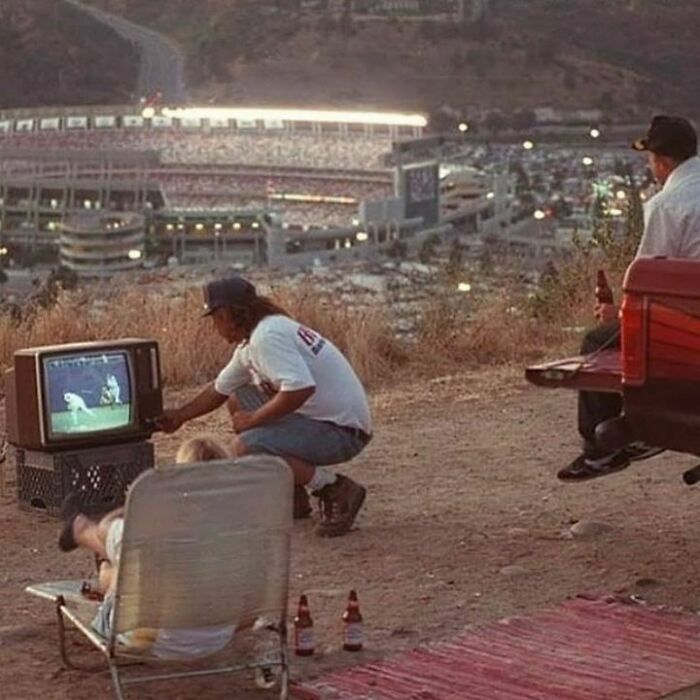

#120 Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game In San Diego, 1992

Image credits: undiscoveredh1story

Recommended Videos

40 Relationship Memes For Anyone Craving Romance231 views

40 Relationship Memes For Anyone Craving Romance231 views The Beautiful Black-Throated Bushtit Bird Is Making Us Wonder ‘Did I Read That Right?’151 views

The Beautiful Black-Throated Bushtit Bird Is Making Us Wonder ‘Did I Read That Right?’151 views-

Advertisements

Meet The Dumbo Octopus That Navigates The Deep Sea With Its Elephant-Ear Fins49 views

Meet The Dumbo Octopus That Navigates The Deep Sea With Its Elephant-Ear Fins49 views 21 Jaw-Dropping Naked Dresses Worn By Celebs That Make Me Do A Double Take Every Darn Time408 views

21 Jaw-Dropping Naked Dresses Worn By Celebs That Make Me Do A Double Take Every Darn Time408 views 30 Prettiest Flowers in the World32 views

30 Prettiest Flowers in the World32 views 9 OF THE BEST WHITE EGGPLANT VARIETIES284 views

9 OF THE BEST WHITE EGGPLANT VARIETIES284 views Discover the Elegance of the Spotted Forktail Bird – Enicurus maculatus25 views

Discover the Elegance of the Spotted Forktail Bird – Enicurus maculatus25 views A Gorilla With A Pink-White Finger Because Of Lack Of Pigmentation On Her Hand48 views

A Gorilla With A Pink-White Finger Because Of Lack Of Pigmentation On Her Hand48 views