Meet the 50 Weirdest Deep Sea Creatures Lurking Beneath the Waves

Scientists know more about space than the ocean, according to Columbia University’s Earth Institute. So in a sense, a majority of the creatures lurking below the surface may as well be aliens. Meanwhile, researchers from Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada believe that 91 percent of these marine animals are still unknown to us.

Of the 235,000 or so species we do know about, many have adapted to their environment with peculiar camouflage, bioluminescence, and mating habits—leading to some seriously strange appearances. These are our 50 favorite deep sea creatures.

1

Peacock Mantis Shrimp

Found in the Indian and tropical western Pacific oceans, the peacock mantis shrimp is a candy-colored crustacean known for its ability to quickly “punch” prey with its front two appendages. According to Oceana, the international ocean preservation advocacy group, this shrimp’s punch is one of the fastest movements in the animal kingdom—so much so, that it’s strong enough to break an aquarium’s glass wall. But no worries: They mostly only use their fists of steel to break open mollusks and dismember crabs.

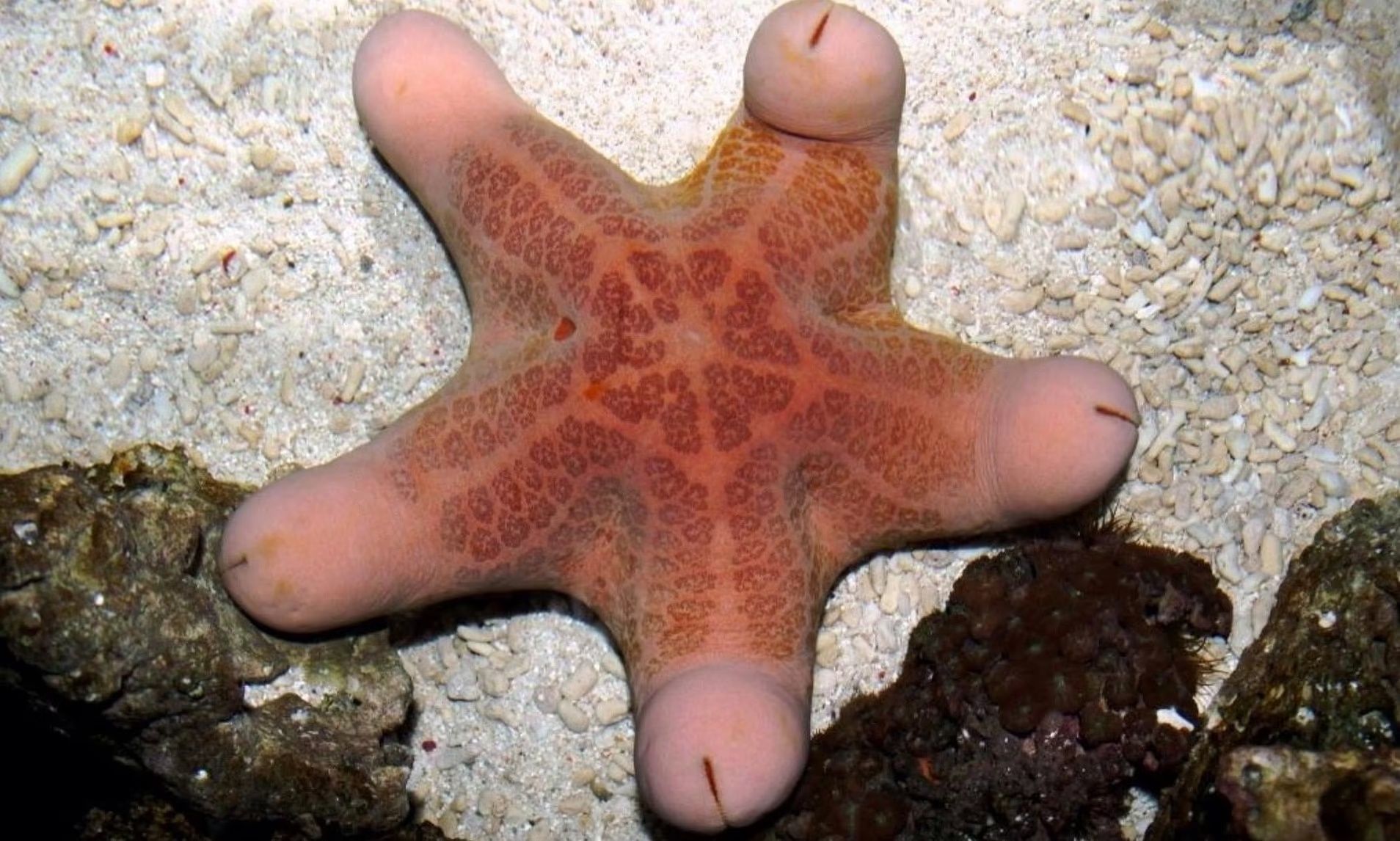

Pink See-Through Fantasia

Its name makes it sound like a piece of sexy lingerie, but don’t be fooled: the pink see-through fantasia is a sea cucumber, found about 1.5 miles deep into the Celebes Sea in the western Pacific, east of Borneo. It was only discovered a little over a decade ago, back in 2007, but the curious sea cucumber has a survival tactic that points to its longtime evolution: bioluminescence to ward off predators. The pink see-through fantasia is named for its transparent skin, through which its mouth, anus, and intestines are all visible.

Frogfish

It’s so easy to miss the frogfish, because these types of anglerfish (there are over 50 species of them) are nearly identical to their surroundings—mostly coral reefs. They resemble sponges or algae-covered rocks and come in pretty much every color and texture imaginable. Some frogfish even use their camouflage not to hide, but rather, to mimic poison sea slugs. No matter their appearance, one thing all species of frogfish have in common is their strange mode of locomotion. Although they can swim, most walk along their pectoral fins, which have evolved into arm-like limbs, including a joint that resembles an elbow.

Ribbon Eel

Usually seen nestled into burrows around coral reefs, the ribbon eel (sometimes called the leaf-nosed moray eel) lives in Indonesian waters from East Africa, to southern Japan, Australia, and French Polynesia. The juveniles start out black, with a pale yellow strip along the fins, and as they grow, transitions to a bright blue and yellow coloring. These eels are considered “protrandic hermaphrodites,” meaning they change sex from male to female several times throughout their lives.

Frilled Shark

The frilled shark, Chlamydoselachus anguineus, is one of the gnarliest looking creatures in the sea. If it looks like an ancient beast, that’s because it is: the prehistoric creature’s roots go back 80 million years. The frilled shark can grow to about seven feet long and is named for the frilly appearance of its gills. Although shark in name, these animals swim in a distinctly serpentine fashion, much like an eel. They mostly feed on squid, usually swallowing their prey whole.

Christmas Tree Worm

Scientists found this strange creature at the Great Barrier Reef’s Lizard Island and named it, aptly, the Christmas tree worm. The spiral “branches” are actually the worm’s breathing and feeding apparatuses, while the worm itself lives in a tube. These tree-like crowns are covered in hair-like appendages called radioles. These are used for breathing and catching prey, but they can be withdrawn if the Christmas tree worm feels threatened.

Box Crab

Like so many other sea creatures, the box crab is a master of disguise. In this case, the crustacean—which mostly keeps to the seabed—buries itself beneath the sand, with just its eyes protruding from the mucky depths. One of the most fascinating aspects of the box crab’s life cycle is its mating habits, which literally redefine what it means to be swept off your feet. When the male box crab has found its mate, it grasps onto her with its claws and carries her around the sea floor until she molts her shell.

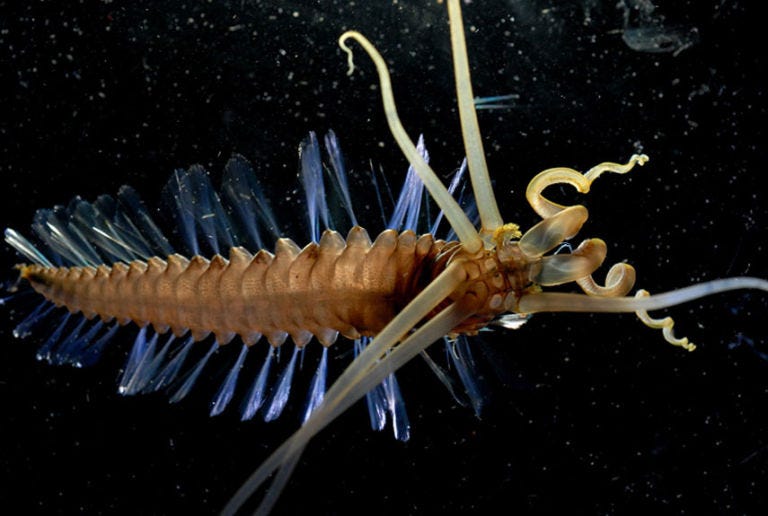

The Squidworm

Researchers with the Census of Marine Zooplankton first discovered the squidworm in 2007 during a cruise in a remotely operated vehicle some 1.8 miles underwater. The funky-looking fish is named for the 10 appendages protruding from its head, which look like tentacles. The squidworm uses these to collect debris falling from the open waters above, known as “marine snow.”

Giant Isopod

These guys are native to chilly, deep waters and can grow to be quite large; in 2010, a remotely operated underwater vehicle discovered a giant isopod measuring 2.5 feet. These crustaceans, which sort of resemble a massive woodworm, are carnivores and usually feed on dead animals that fall down from the ocean’s surface. Despite their discovery back in 1879, these creatures mostly remain a mystery. However, it’s believed that giant isopods grow so large in order to withstand the pressure at the bottom of the sea.

Nudibranch

With over 3,000 different species on record, the nudibranch is an extremely versatile kind of sea slug. These little guys are found pretty much everywhere, in both shallow and deep waters, from the North and South poles and into the tropics. There are two distinct kinds: dorid nudibranchs, which are smooth with feather-like gills on their back to help them breathe; and aeolid nudibranchs, which breath through a different kind of organ, also located on their backs, called cerata. Because the tiny nudibranch lacks a shell, it instead protects itself with bright camouflage, meant as a warning signal. But perhaps their wildest adaptation of all is the ability to quite literally swallow, digest, and reuse stinging cells from prey.

✅ Dive Deeper: Some Fish Can Count, But No One Knows Why

Sea Angel

Although they’re called sea angels, these creatures are actually predatory sea snails. This particular specimen, Platybrachium antarcticum, “flies through the deep Antarctic waters hunting the shelled pteropods (another type of snail) on which it feeds,” according to the Marine Census of Life. Sea angels have special parapodia, or lateral extensions of the foot, that help to propel them through the water.

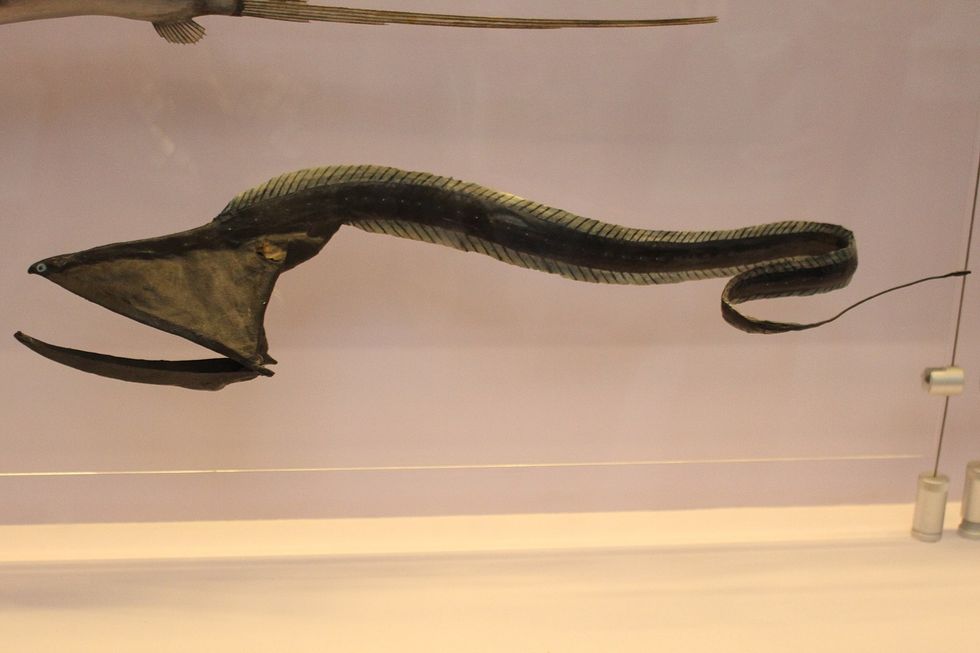

Gulper Eel

The gulper eel (also referred to as the pelican eel) is named for its massive mouth and jaw, which helps them to swallow prey whole. They can grow up to six feet in length and their huge mouths allow them to hunt down meals that are larger than them. This usually happens when food is scarce—it’s believed that gulper eels usually eat crustaceans and other small marine animals.

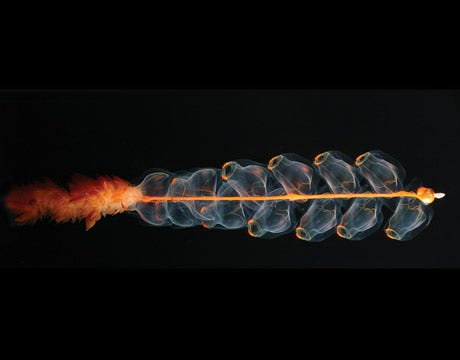

Marrus Orthocanna

Like a multi-stage rocket, this bizarre microscopic creature, Marrus orthocanna is made up of multiple repeated units, including tentacles and multiple stomachs. Technically, they are physonect siphonophores, which are related to the Portugese man o’war. Like ants, a colony made up of many individuals has attributes resembling a single organism.

Giant Squid

The Giant Squid, Architeuthis dux, is absolutely the stuff of nightmares. The largest one ever recorded came in at a whopping 43 feet long—nearly half the size of a blue whale. Earlier this year, scientists created a draft genome sequence for the giant squid, in a bid to better understand it. With about 2.7 billion DNA base pairs, its genome is about 90 percent the size of the human genome. Beyond that, scientists don’t know a whole lot about the giant beast or its habits, because most of what we know comes from their carcasses, which wash up on the shore. Most of the time, the giant squid lives in waters so deep that we never see them, adding to their intrigue.

Munnopis Isopod

A virus? An alien? Nope. It’s a Munnopsis isopod crustacean, and even scientists haven’t figured out more than that about this deep Southern Ocean denizen, yet. Isopods are ancient creatures (they’ve been on Earth, in one form or another, for 300 million years or so) with no backbones that have seven pairs of legs. On land, you might be familiar with their cousin, the pill bug.

Red-lipped Batfish

This bizarre-looking fish is also known as the Galapagos batfish and can be found at the bottom of the ocean. It’s named for its red lips, which make it appear to be wearing lipstick. Although the red-lipped batfish appears to have legs, its limb-like appendages are actually fins, which the creature uses to stand on and to check out its surroundings.

Armored Snail

There’s no other snail in the world armored like the Crysomallon squamiferum, which lives over hydrothermal vents deep in the Indian Ocean. It goes by quite a few other names, including the “scaly-foot gastropod,” “scaly-foot snail,” and even the “sea pangolin.” Today, its multilayered shell structure is inspiring stronger materials, from airplane hulls to military equipment.

Bioluminescent Octopus

One of the few known octopods known to use bioluminescence (or glowing with its own light), the Stauroteuthis syrtensis octopus lives about one mile deep in the Gulf of Maine. It can position its photophores (light-emitting organs) to fool prey into swimming right into its mouth.

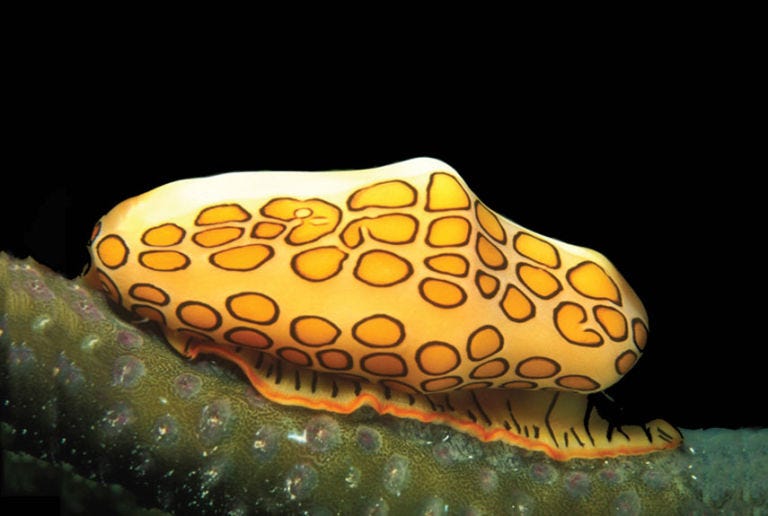

Flamingo Tongue Snail

With a name like flamingo tongue snail, and the flamboyant coloration to match, you might think this Cyphoma gibbosum has a shell worthy of collecting. Not so. All of the flamingo tongue snail’s color comes from the soft parts of its body, which envelop its shell. When threatened, it can retract its mantle flaps, exposing its true shell.

Vampire Squid

Strangely enough, this form of sea life is neither a squid, nor an octopus, despite its appearance. Scientists have designated the vampire squid as a completely separate animal, even though it has eight arms and two tentacles. Again, the name can be confounding—these creatures don’t suck blood and actually are pretty passive hunters, considering they’re filter feeders. Instead, the name comes from the skin between its arms, which resembles a cape. Oh yeah, and this little dude lives in the pitch black waters of the mesopelagic zone.

Coffinfish

Also known as “the sea toad,” these deepwater fishes are relatives of the frogfish (see slide 3). These creatures have a small lure, protruding from a depression behind their eyes. Coffinfish use it to lure prey toward them, and because there is so little light at the depths where they live, it allows them to quickly attack. According to Smithsonian Magazine, these fish also “boast such sizable gills that they can increase their body volume by up to 30 percent upon inhaling a significant quantity of water.” That would be the equivalent of a human inflating their lungs to become the size of their full abdomen—not exactly possible.

Leafy Seadragon

Found along the southwestern coast of Australia, the leafy seadragon, Phycodurus eques, uses its fins not only to propel itself through the water, but as camouflage to resemble a piece of drifting seaweed. Because they have pretty big heads compared to the rest of their body, leafy seadragons are able to concentrate pressure at their mouth to suck in prey. Similar to seahorses and pipefishes, the males carry around fertilized eggs. But without a special pouch, the leafy seadragon carries the eggs beneath its tail.

Blobfish (aka Fathead)

Scientists call this fish Psychrolutes microporos, but also, more directly, “Fathead.” Smithsonian Magazine even notes that the weird looking creature is largely considered the “World’s Ugliest Animal.” But the blobfish is a pretty incredible sea dweller, surviving at depths in excess of 4,000 feet, where the pressure is 120 times higher than at the surface. And here’s the thing: the blobfish is only actually ugly when it’s brought up to the surface. Most fish have a swim bladder, or a sac of air inside its body to keep buoyant. When fish are removed from their typical environments, these sacs swell up, leading to the innards pushing out through the mouth. Technically, we only think of the blobfish as ugly when it’s dead—so maybe think twice before pointing and laughing.

Crossota Norvegica Jellyfish

Known for its vibrant red coloring, the Crossota norvegica is a kind a jellyfish, collected from the deep Arctic Canada Basin. It lives about 2,500 meters beneath the surface, and uses ectodermal cells with nematocysts to sting prey. It’s not exactly clear what these creatures feed on, but it’s most likely a combination of zooplankton and phytoplankton.

Yeti Crab

This furry-clawed crab looks so unusual that when scientists discovered it 5,000 feet deep on a hydrothermal vent south of Easter Island, they designated it not only a new genus, Kiwa, but a new family, Kiwidae—both named for the mythological Polynesian goddess of shellfish. It’s likely blind and may use bacteria in its furry claws to detoxify its food.

Jawfish

Let’s state the obvious: this thing looks like it’s throwing up. But what you’re actually seeing is the strange mating process of the jawfish, a species native to coral reefs in the Caribbean Sea and western Atlantic. Beyond using their jaws to scoop up sand, the males also use their huge mouths to carry eggs until they hatch. Still, other times, their mouths are like weapons, used in jousting matches—the jawfish truly puts its money where its mouth is.

Vigtorniella Worm

What do you get when a whale dies at sea? You get a feast, if you’re a polychaete worm, like this newly discovered Vigtorniella, found a about a half mile below sea level in Sagami Bay, Japan.

Goblin Shark

Long story short: Goblin sharks look scary as hell. The super-rare creature can grow up to 15 feet in length and has the ability to thrust its whole jaw outward in order to capture prey. Fewer than 50 goblin sharks have been spotted since 1898, so if you’re hoping to see one, chances are slim.

Terrible Claw Lobster

Named Dinochelus ausubeli for its “terrible or fearful” (dinos in Greek) claws (chela), this new species of blind lobster joins a very small list of cousins in the genus Thaumastochelopsis. Only four other individuals, in two species, had been found previously, both in Australia. Scientists collected the specimen during the Aurora mission in 2007, led by the U.S. and French natural history museums, and the Philippines Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. That second part of its name, ausubeli is also significant: It’s in honor of Jesse Ausubel, a co-founder of the Census of Marine Life.

Pycnogonid Sea Spider

Found in the Antarctic, this male pycnogonid spider (or a distant relative of a spider, anyway) bears its own eggs. It has virtually no abdomen, yet has a leg span of about 25 centimeters, which means it’s about on par, size-wise, with some of the largest spiders on land, like the Goliath Bird-Eating tarantula of South America.

Whitemargin Stargazer

Perhaps the only other fish that could contend with the blobfish for the ugliest creature in the sea, the whitemargin stargazer is a real tough guy that uses double-grooved poison spines above its pectoral fins to sting pray. As if that weren’t enough, the stargazer also has electrical organs, contained in a special pouch behind its eyes, that allow it to sting prey with up to 50 volts. As for its name, the stargazer spends most of its time burrowed in the sand, with only its eyes protruding up to toward the surface.

The Dumbo Octopus

This Grimpoteuthis octopus, found over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, is affectionately called Dumbo because of the way it flaps its ear-like fins to swim. Dumbo octopuses are known to be the deepest-dwelling of the octopuses, as they live at depths of at least 4,000 meters, but often even deeper than that. Because these octopuses are naturally rare, they’ve developed unique breeding habits to increase the chances of producing offspring. For example, the females carry eggs at various stages of development and can even store sperm inside their bodies for long periods of time after mating.

Arctic Hydromedusa

This hydromedusa, Bathykorus bouilloni, is common in the deep waters of the Arctic, about 3,300 feet deep. The broader family of hydromedusae are so common, in fact, that they compose the largest group of cnidarians in the sea. Coming in at just a few millimeters to a few centimeters at absolute maximum size, though, they’re far smaller than your typical jellies. But what really sets them apart from the jellyfish is their reproductive system: Hydromedusae produce both sperm and eggs outside of the body, underneath their squishy bell.

Obese Dragonfish

Hey! That’s not nice! But in all seriousness, the obese dragonfish surely won’t take offense to its name—after all, there’s no shame in being one of the largest species in the family Melanostomiidae. In fact, it’s actually pretty badass. According to the Australian Museum, these deepwater dwellers feature a smooth, scaleless black body, boast a full set of large fang-like teeth, plus a long chin barbel, and a series of light-producing photophores along the body and behind both eyes. For the most part, these guys stick to the waters around Australia, but can also be found in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans.

Hydrothermal Vent Snail

Another hydrothermal vent snail, this Alviniconcha snail was found at the Suiyo Seamount of the Tokyo Hydrothermal Vent. It’s the only individual of its kind ever discovered.

Red-Spotted Blenny

These algae-munching fish are mostly known to be peaceful, but when it comes to other members of their species—or at least those who aren’t their own mates—the Red-Spotted Blenny can be hostile, especially if kept in a tank. Just like tangs, they sometimes bite or full-on attack other nearby Red-Spotted Blenny fish; they even take nibbles at corals and clams at times. Their native habitats are along coral reefs in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

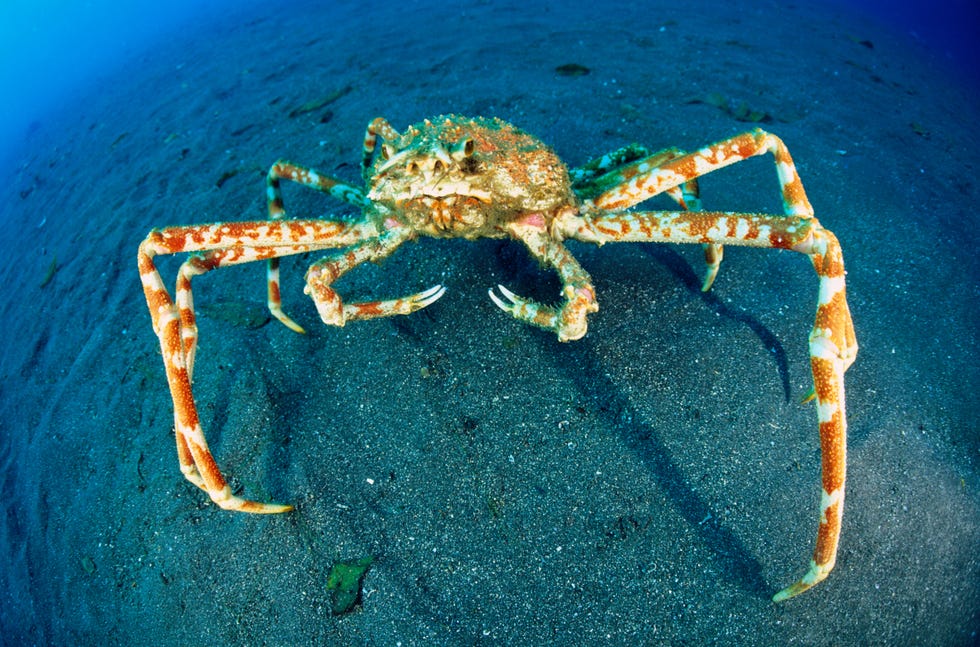

Japanese Spider Crabs

These giant crabs are, as their name indicates, native to Japan and are considered delicacies throughout the country. These guys can grow to be up to 12 feet long and they are not picky eaters. In fact, the Japanese spider crab is believed to favor eating the bodies of other marine animals because it means they don’t have to kill anything themselves.

Squirrelfish

The squirrelfish can only reach a max length of about two feet, but this creature packs some serious punch in its relatively small frame. Mostly nocturnal, these fish live at depths of between 100 and 600 feet below the surface, where they scan the sandy sea floor and grass beds for prey. The coolest thing about them? They can actually use their swimbladder to produce sounds for communication between other squirrelfish.

Porcupinefish

Similar to their cousin, the puffer fish, the porcupinefish is covered in strong spines and has the ability to swallow up water to puff up its body into an orb when threatened. This is helpful because it’s pretty much impossible for predators to swallow a porcupinefish in full-on balloon mode. Even if a predator does manage to swallow it before it has the chance to puff up, it’s still poisonous to most fish, meaning it’s not a very good snack.40

Delicate Claw Crustacean

This newly discovered species of crustaceans, known for its delicate claws, Leptocheliidae sensu lato, was found near the Great Barrier Reef’s Lizard Island.

Mimic Octopus

Found in the Indo Pacific, the mimic octopus is not only known for its ability to use chromatophores to blend in with the surroundings, but also its skill in impersonating a number of other marine animals—hence the name. Among the animals it mimics to defend itself from predators are the lion fish, sea snake, jellyfish, and zebra sole. Other times, the mimic octopus uses its shapeshifting abilities to approach prey, sometimes even appearing as a crab’s intended mate before chowing down.

Thornback Cowfish

Technically a kind of boxfish, this guy has horns at the top of his head, but doesn’t use them to bully others. However, in stressful environments—or if it dies—the thornback cowfish can become toxic.

Lysianassoid Amphipod

One of many new amphipods discovered by the Marine Census of Life, this Lysianassoid amphipod inhabits the waters near Elephant Island in the Antarctic. Like other tiny crustaceans, amphipods (A.K.A. sea fleas) are a big source of food for larger creatures of the deep.

Parrotfish

Ranging from about one foot to four feet in length, there are approximately 80 different species of parrotfish in an array of colors, scattered across coral reefs around the world. Their name comes from the fused teeth at the front of their mouth, which resembles a beak. Incredibly, their scales are so tough that in some cases, even spears can’t pierce through them.

Sea Pen

The orange sea pen, Ptilosarcus gurneyi, is actually a colony of animals that can withdraw into the soft sediment where it’s found. Generally speaking, there are over 300 species of sea pens, named for their quill-like appearance. With stimulation, they glow with a green light.

Metapseudes

This potentially new species of Metapseudes was found in abundance among the coral rubble at Ningaloo, Western Australia. What is it, exactly? Well, it’s an arthropod, meaning it’s somewhat related to insects, crustaceans, spiders, scorpions, and centipedes. Of course, that’s not saying much, since there are more arthropod species on Earth than all other phyla combined.

Napolean Wrasse

You can’t really beat the description of this creature from the Census of Marine Life: “Exceeding two meters in length, the Napoleon Wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus) is one of the largest reef fish found in the warm waters of the Indian and Pacific oceans. The intricate blue-green design that decorates the face resembles New Zealand Maori war paint, which is the root of its alternative name, the Maori Wrasse. The designs are also unique to each individual, much like fingerprints. A protogynous hermaphrodite, this wrasse can change its sex from female to male.”

Sea Nettles

The image of swarms of sea nettles, like these Chrysaora fuscescens in Monterey Bay, California, is so intense that they’ve been bred for aquariums. They do have a sting, though it’s rarely a health risk for humans.

Venus Flytrap Anemone

This Venus flytrap anemone of the genus Actinoscyphia was found in the Gulf of Mexico. Related to jellyfish, sea anemones get their name from the flower of the same name. This creature, in particular, closes its tentacles to capture prey or to escape predators.

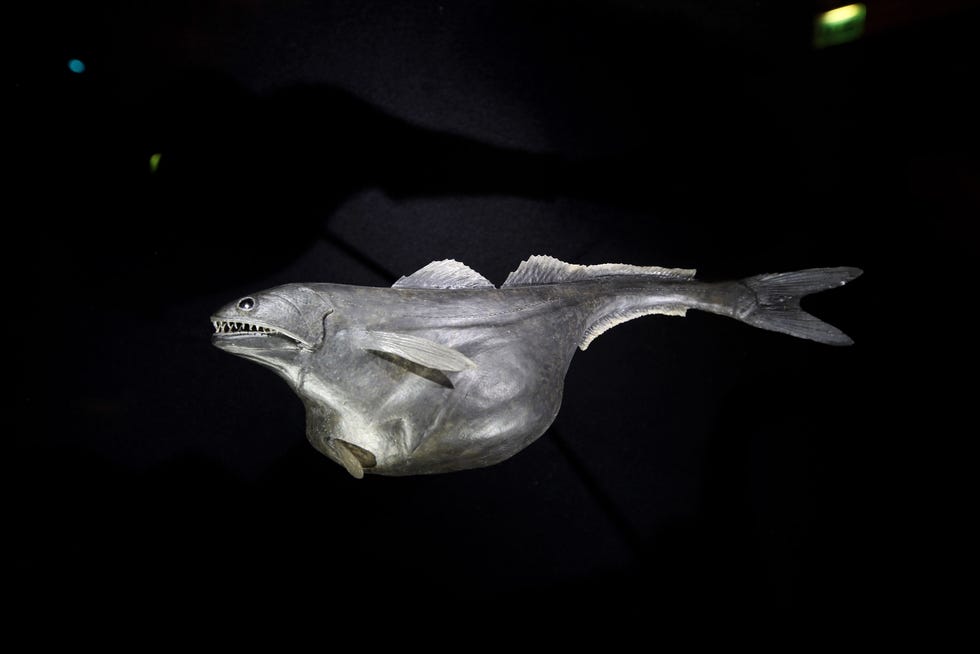

Black Swallower

The black swallower fish has the ability to swallow prey much larger than itself thanks to the extended gut attached to its belly. This adaptation is especially useful since black swallowers live in the deep and food can be scarce to come by in the abysmal depths of the sea.

Recommended Videos

“Draco” Also Known As Flying Dragons Exist And They Are A Real Wonder of Nature105 views

“Draco” Also Known As Flying Dragons Exist And They Are A Real Wonder of Nature105 views THESE terrifying images of muscle-bound chimps show why we should all pray the apes don't ever try to take over the world...1161 views

THESE terrifying images of muscle-bound chimps show why we should all pray the apes don't ever try to take over the world...1161 views-

Advertisements

Bat Flower Care – Tips For Growing Tacca Bat Flowers1358 views

Bat Flower Care – Tips For Growing Tacca Bat Flowers1358 views Rivoli's hummingbird (Eugenes fulgens) is a large hummingbird.311 views

Rivoli's hummingbird (Eugenes fulgens) is a large hummingbird.311 views Pictures Of A Lizard That Fell Asleep Inside A Rose61 views

Pictures Of A Lizard That Fell Asleep Inside A Rose61 views These 30 Masterclass Jewelry Tattoos By Celebrity Ink Artist Ryan Ashley Might Be Better Than The Real Thing3143 views

These 30 Masterclass Jewelry Tattoos By Celebrity Ink Artist Ryan Ashley Might Be Better Than The Real Thing3143 views The wire-tailed manakin (Pipra filicauda) is a species of bird in the family Pipridae.1478 views

The wire-tailed manakin (Pipra filicauda) is a species of bird in the family Pipridae.1478 views Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa)403 views

Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa)403 views