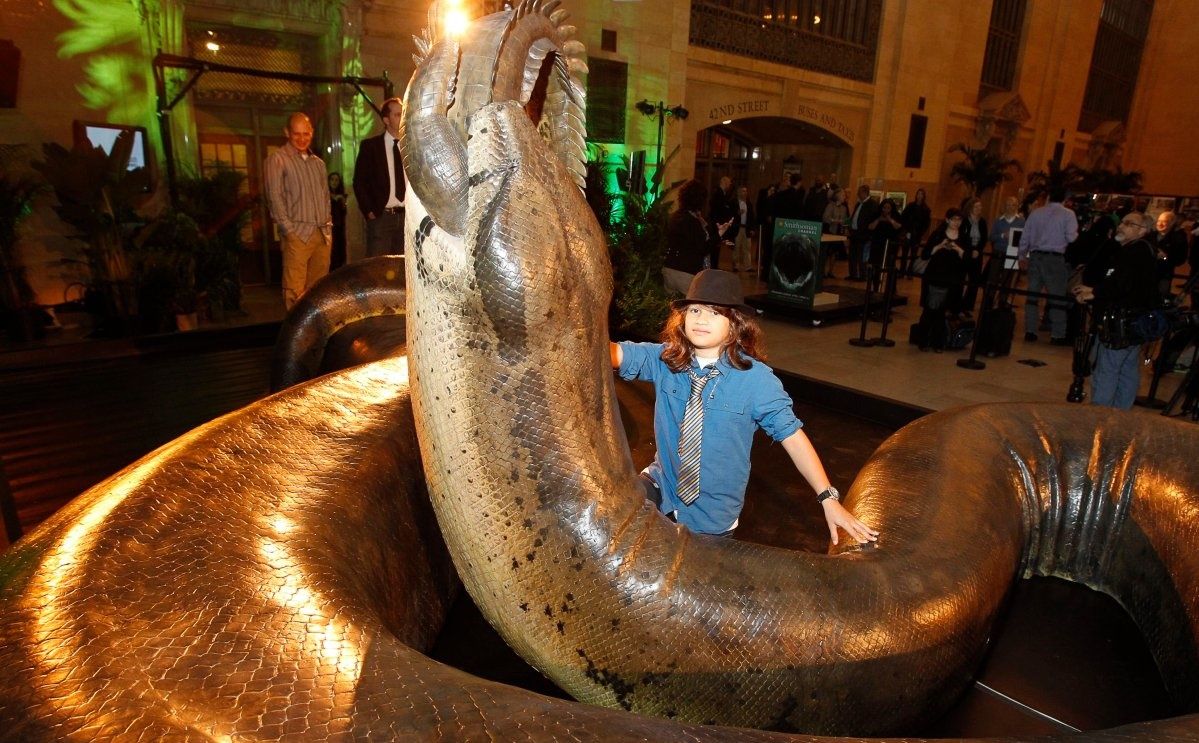

Meet Titanoboa, the Largest Snake to Have Ever Roamed the Earth

ome of creatures that lived on our planet millions of years ago were so huge and impressive that they would make today’s animals look like dwarfs. One of these ancient giants was Titanoboa, the biggest snake to have ever roamed the earth.

Titanoboa was a genus of extinct boid snake that lived during the Paleocene epoch, about 60 to 58 million years ago, in what is now northeastern Colombia. The name Titanoboa means “titanic boa”, and it was indeed a colossal reptile. It could grow up to 12.8 meters (42 feet) long, perhaps even 14.3 meters (47 feet) in some cases, and weigh up to 1,135 kilograms (2,500 pounds). That’s more than twice as long and five times as heavy as the largest living snake, the green anaconda.

Titanoboa was first discovered in the early 2000s by a team of scientists from the University of Florida and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, who found several fossils of its vertebrae and ribs in the coal mines of Cerrejón, Colombia. Later, they also found parts of its skull and teeth, which revealed more details about its appearance and lifestyle.

Cerrejón is situated in the lowland tropics of northern Colombia, 60 miles from the Caribbean coast, and is one of the globe’s wealthiest fossil deposits. It offers a distinct glimpse into the geological transition following the extinction of dinosaurs, and stands as the premier, and possibly sole, portal to an entire ancient tropical ecosystem worldwide.

The fossils at Cerrejón were nearly missed by scientists until an observant undergraduate identified a significant number of sandstone impressions of fossil leaves. This discovery prompted an expedition that unveiled numerous new species, including the largest snake ever recorded in history.

Titanoboa had a robust and wide body, with a pentagonal shape in cross-section. Its head was relatively small compared to its body, and its eyes were located on the top of its skull, suggesting that it spent most of its time submerged in water. Its teeth were curved and sharp, adapted for grabbing and holding slippery prey.

The color and pattern of Titanoboa’s skin are unknown, but it is possible that it had dark and light markings to camouflage itself in the swampy environment. Some scientists have also speculated that it had heat-sensing pits on its snout, like modern boas and pythons, to detect warm-blooded animals in the dark.

Titanoboa was a carnivorous predator that fed mainly on fish. Its skull bones indicate that it had a powerful bite force and a flexible jaw that could swallow large prey whole. It probably hunted by ambushing its victims from the water or the shore, coiling around them and suffocating them with its muscular body.

Titanoboa’s prey included lungfish, crocodiles, turtles, and even smaller snakes. It had no natural enemies, except perhaps for other Titanoboas. It was the apex predator of its ecosystem, dominating the food chain.

How strong was Titanoboa exactly? Well, here’s the ultimate battle of the predators – the monster snake against a T-Rex! They lived in different times and places, but if they ever met, which of them would win?

Titanoboa’s size was not only impressive but also informative. It revealed that the climate of the Paleocene epoch was much warmer than today’s. This is because snakes are ectotherms, meaning that they rely on external sources of heat to regulate their body temperature. The larger a snake is, the more heat it needs to maintain its metabolism and activity.

Scientists have estimated that Titanoboa required an average annual temperature of 30 to 34 degrees Celsius (86 to 93 degrees Fahrenheit) to survive. This means that the tropical regions of South America were about 4 degrees Celsius (7 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than they are now. This also implies that there was a higher concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which caused a greenhouse effect.

Titanoboa’s fossils provide valuable clues about how life evolved and adapted after the mass extinction event that wiped out most of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. They also show us how climate change can affect biodiversity and ecosystems in profound ways.

Recommended Videos

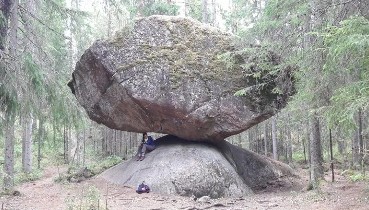

“Kummakivi” – A Timeless Wonder of Nature: The Unwavering Balance of Oddstone60 views

“Kummakivi” – A Timeless Wonder of Nature: The Unwavering Balance of Oddstone60 views The rufous fantail (Rhipidura rufifrons) is a small Passerine bird1730 views

The rufous fantail (Rhipidura rufifrons) is a small Passerine bird1730 views-

Advertisements

A Startled Owl Puffs Up to Appear Much Larger In Order to Intimidate an Equally Defensive Family Cat209 views

A Startled Owl Puffs Up to Appear Much Larger In Order to Intimidate an Equally Defensive Family Cat209 views 45 Of The More Rare And Extraordinary Dog Breeds171 views

45 Of The More Rare And Extraordinary Dog Breeds171 views Most Incredible Winners Nature Photography118 views

Most Incredible Winners Nature Photography118 views Shelf Cloud versus a Wall Cloud39 views

Shelf Cloud versus a Wall Cloud39 views Try One of These 10 Home Remedies for Toenail Fungus4918 views

Try One of These 10 Home Remedies for Toenail Fungus4918 views We’ve all seen fireflies on hot summer nights in Iowa, but have you ever come across a GLOWWORM?271 views

We’ve all seen fireflies on hot summer nights in Iowa, but have you ever come across a GLOWWORM?271 views