Robert Landsburg was a 48-year-old photographer from Portland who died when Mount St. Helens erupted.

On May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens in southwestern Washington erupted, killing 57 people. One of those victims was Robert Landsburg, a photographer who had been documenting the volcanic activity in the weeks prior to the eruption.

Landsburg was about four miles west of Mount St. Helens when it exploded, but the pyroclastic flow traveled so quickly that he barely had time to react before it reached him. In his final moments, Landsburg snapped a few stunning images of the approaching ash cloud, rolled up his film, and used his body to shield it from the heat.

Rescuers pulled Landsburg from the debris 17 days later. He’d died as soon as the hot ash reached him — but his photographs survived.

Today, Landsburg’s final photos are among the most haunting images captured on the day Mount St. Helens erupted.

The 1980 Eruption Of Mount St. Helens

In March 1980, seismographs picked up small tremors beneath Mount St. Helens, an active volcano in southwestern Washington that’s part of the Cascade Range. Over the next two months, scientists, photographers, and curious hikers flocked to the area in hopes of seeing an eruption.

Among them was Robert Emerson Landsburg, a 48-year-old freelance photographer from Portland, Oregon. He visited the volcano numerous times in the weeks leading up to the disaster, documenting any changes he noticed, such as the large bulge that appeared on the mountain’s northeastern slope as pressure built below the surface.

On the night of May 17, Landsburg set up camp near Mount St. Helens in preparation for another day of hiking and taking photos. That evening, according to the book Eruption: The Untold Story of Mount St. Helens, he wrote in his journal, “Feel right on the verge of something.”

A volcanologist with the U.S. Geological Survey named David Johnston was also closely watching Mount St. Helens. When a 5.1-magnitude earthquake struck at 8:32 a.m. on May 18, just hours after Landsburg’s ominous journal entry, Johnston knew disaster was imminent. He grabbed his radio and shouted, “Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!”

U.S.G.S.Geologist David Johnston watched the volcano erupt before he was killed by the pyroclastic flow.

Right in front of Johnston, Landsburg, and countless onlookers, the northern face of the volcano appeared to liquefy. The bulge vanished as the mountain released 24 megatons of thermal energy — equivalent to 1,600 of the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima.

The pyroclastic flow exploded from the volcano at 400 miles per hour, quickly enveloping Johnston. It also overtook a ham radio operator named Gerry Martin, who watched the cloud destroy Johnston’s station before saying, “It’s going to get me, too.”

According to Scientific American, a geology student named Catherine Hickson was nine miles from Mount St. Helens when it erupted. She later recalled, “All hell broke loose… An incredible black cloud was cascading down the mountainside, fed by the billowing columns soaring upwards into a huge mushroom cloud.”

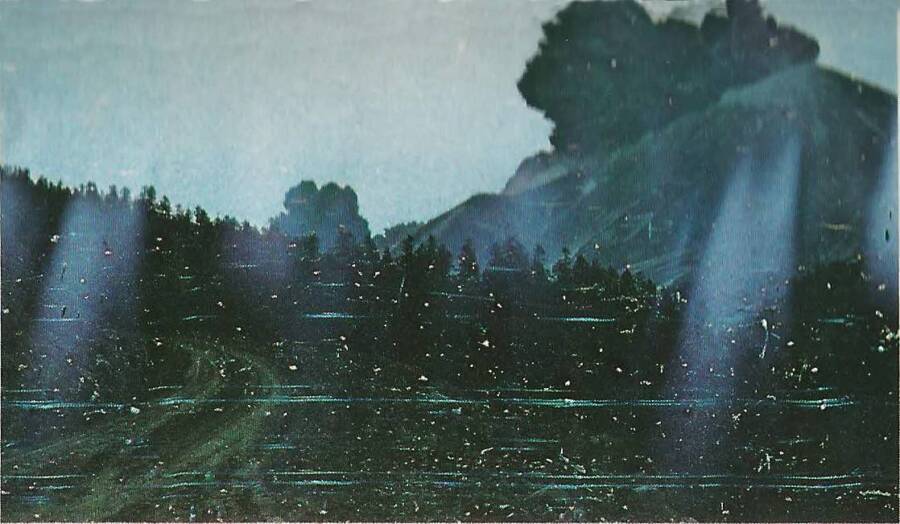

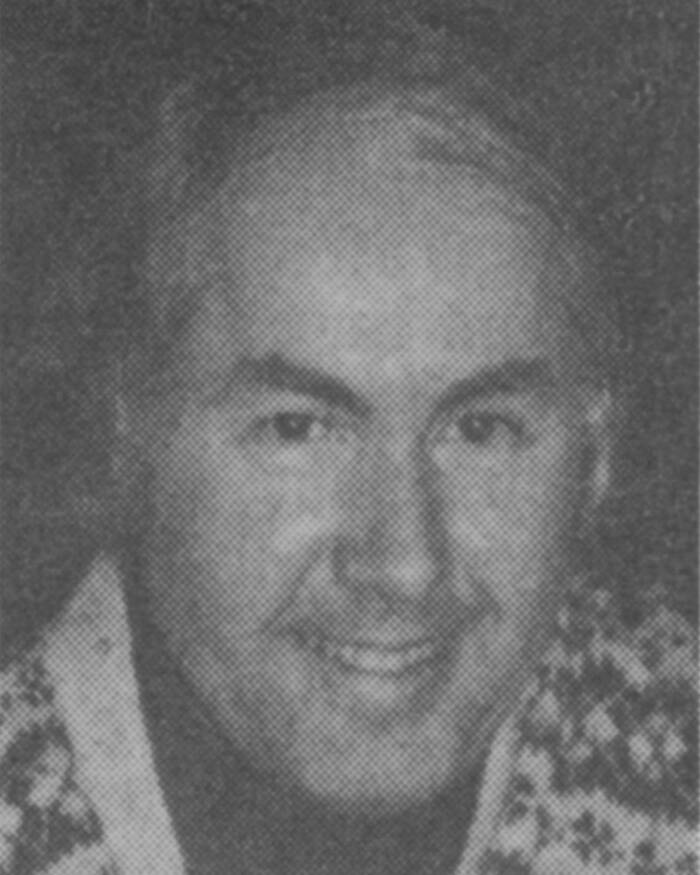

Wikimedia CommonsIn the first of a series of photographs, Landsburg captured the initial blast at 8:32 a.m. on May 18, 1980.

Robert Landsburg was five miles closer to the volcano than Hickson. He had risen early that morning, and he already had his camera out at 8:32. When the earthquake struck, Landsburg had just seconds to react.

Robert Landsburg’s Final Photographs

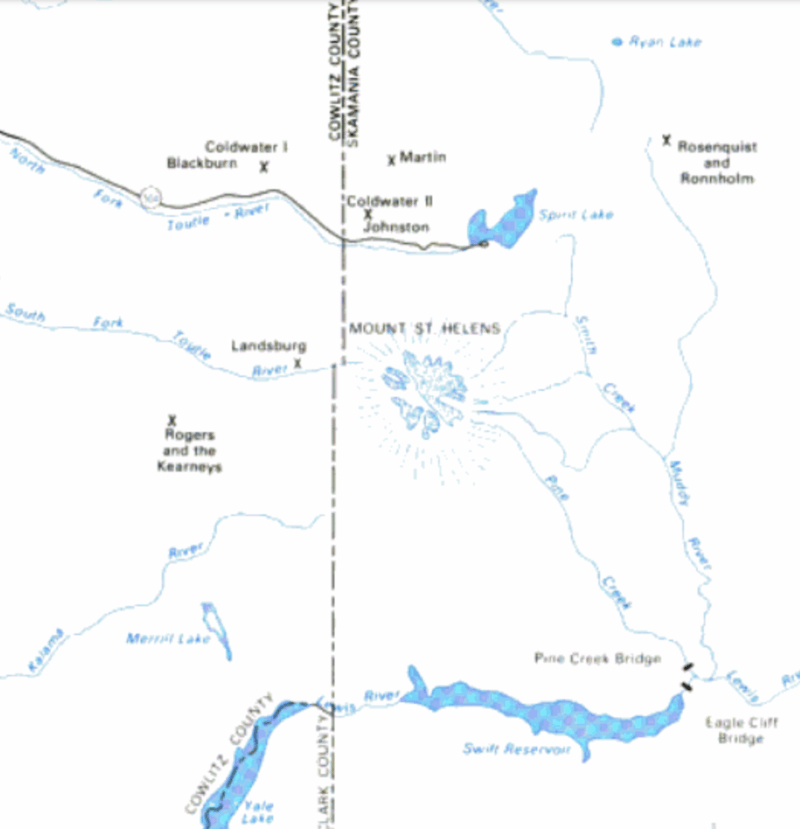

On the morning of May 18, Robert Landsburg had driven his station wagon to the South Fork of the Toutle River. When the volcano erupted, he was less than four miles from the summit.

Wikimedia CommonsThe ash cloud grew quickly, ultimately reaching a height of 80,000 feet.

He was well outside the red zone, where the U.S. Forest Service had restricted travel to scientists and law enforcement. But the blast was larger than anyone had predicted.

Unable to outrun the deadly cloud of ash, Robert Landsburg started snapping photos while retreating to his car. And even as he realized the end was near, he refused to put down his camera.

Landsburg’s car offered little protection from the massive ash cloud, which reached temperatures as high as 800 degrees Fahrenheit. But the photographer wanted to protect the delicate film that he’d just shot.

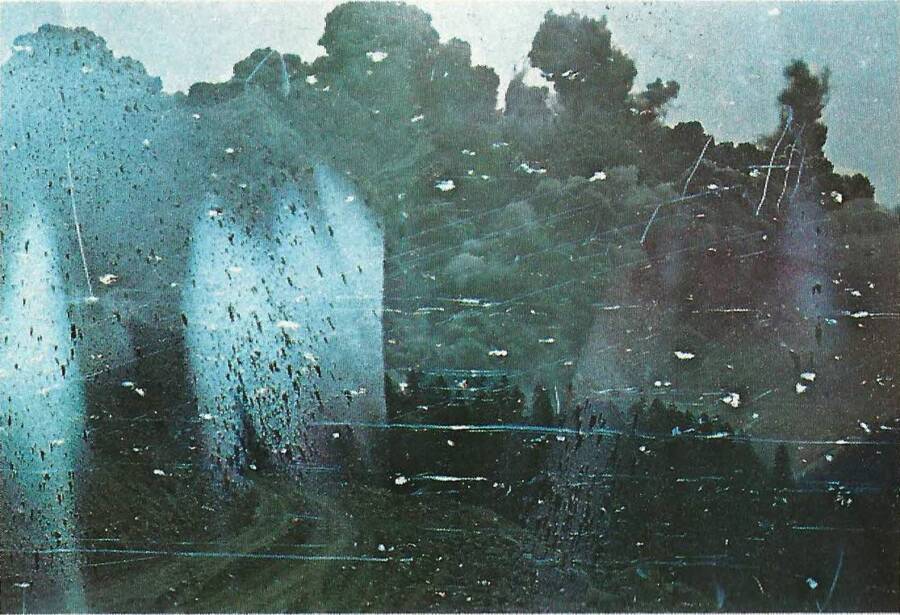

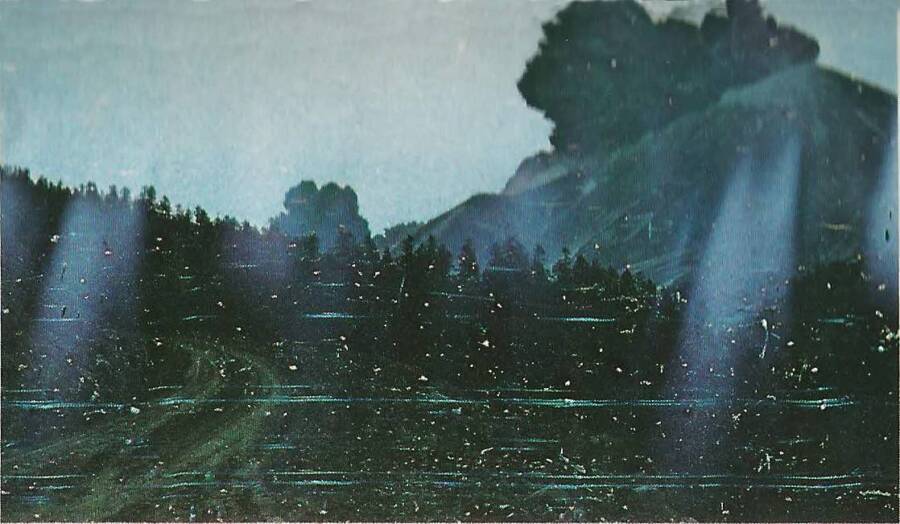

Wikimedia CommonsWithin seconds, the ash had nearly blacked out the sky from Landsburg’s position four miles from the summit.

After taking his final photograph, Landsburg removed the roll of film from his camera and placed it in a canister. He buried the camera and the film canister deep in his backpack. Then, he placed the backpack on the seat next to him and covered it with his body.

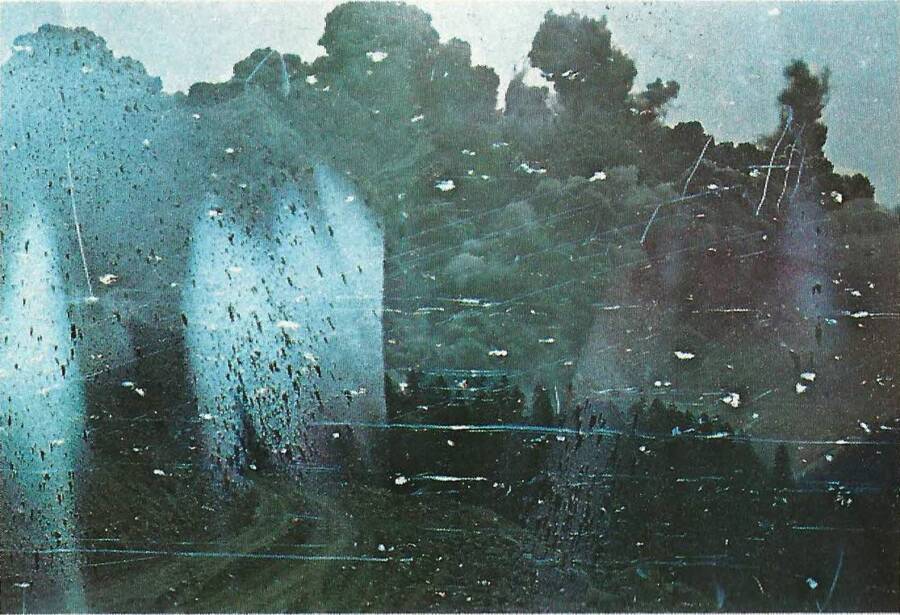

Wikimedia CommonsThe final photograph captured by Robert Landsburg shows the ash reaching his location.

When the blast reached Landsburg, just seconds after the side of the mountain collapsed, it killed him instantly. His official cause of death was asphyxiation by volcanic ash. But thanks to his quick thinking, he left behind a stunning legacy.

Recovering The Images Of The Volcanic Eruption

The eruption of Mount St. Helens covered the surrounding area in thick mudflows, ash, and fallen trees. Rescuers initially focused on locating survivors. Soon, however, efforts shifted to recovering remains.

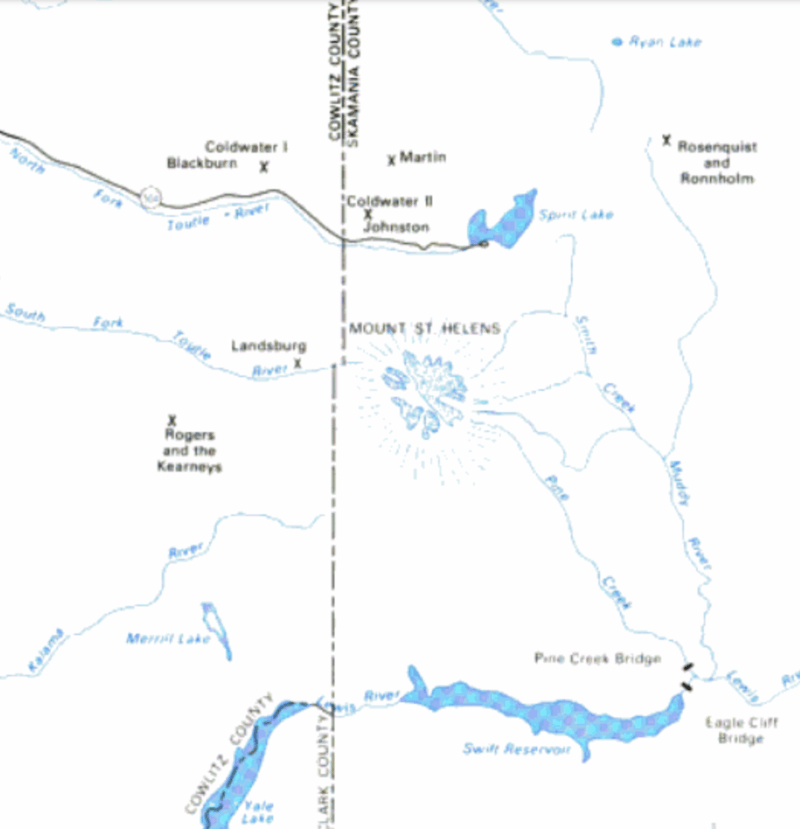

U.S.G.S.A U.S.G.S. map shows the location of Landsburg, Blackburn, Johnston, and others caught in the blast.

Photographer Reid Blackburn had been camping a few miles north of Landsburg when Mount St. Helens erupted. Like Landsburg, Blackburn snapped multiple photographs as the billowing ash cloud overtook his campsite.

However, when rescuers reached Blackburn’s car seven days later, the film had been destroyed.

U.S. Forest ServicePhotographer Reid Blackburn’s car was discovered buried in mud and ash.

Then, in early June 1980, a fellow photographer attempted to recover a remote-activated camera that Blackburn had stationed three miles north of the summit. Hovering from a helicopter, Fred Stocker dug through the mud, searching for the camera.

“I dug around for 45 minutes and got the camera,” Stocker told the Spokane Daily Chronicle at the time. “It was buried under two-and-a-half feet of ash and mud.”

But the film inside the melted camera could not be developed.

U.S.G.S.Reid Blackburn’s camera was recovered from the blast zone, but the film could not be developed.

Rescuers found Robert Landsburg’s car on June 4, 1980 — and in it the roll of film that he had protected with his body. Thanks to his quick thinking under unimaginable distress, the photographs he’d taken of the eruption were actually salvageable.

The film was developed within weeks, and the photos revealed a dark cloud growing larger in every frame. National Geographic published the haunting images in January 1981, sharing Landsburg’s final moments with the world.

After learning about Robert Landsburg and his death during the eruption of Mount St. Helens, check out more photos of volcanic eruptions from around the world. Then, read the tragic story of Omayra Sánchez, the Colombian teenager whose final moments were photographed after she was trapped in debris from an erupting volcano.

A female Brazilian gardener has uncovered the mystery of an uncommon fruit.463 views

A female Brazilian gardener has uncovered the mystery of an uncommon fruit.463 views The king vulture (Sarcoramphus papa) is a large bird found in Central and South America.392 views

The king vulture (Sarcoramphus papa) is a large bird found in Central and South America.392 views This Rare And Horrifying Megamouth Shark Washed Up On A Beach In The Philippines222 views

This Rare And Horrifying Megamouth Shark Washed Up On A Beach In The Philippines222 views Top 10 most rare flowers and what makes them special530 views

Top 10 most rare flowers and what makes them special530 views This Fluffy Little Bird Looks Like A Small Dragon125 views

This Fluffy Little Bird Looks Like A Small Dragon125 views 33 Times People Witnessed Something Interesting At The Beach And Just Had To Share It2704 views

33 Times People Witnessed Something Interesting At The Beach And Just Had To Share It2704 views Artist Brian Mock Takes Scrap Metal And Turns It Into Beautiful Sculptures..525 views

Artist Brian Mock Takes Scrap Metal And Turns It Into Beautiful Sculptures..525 views Orange Fruit Dove1651 views

Orange Fruit Dove1651 views