Take A Journey Back: 85 Vintage Photos Capturing “The Golden Age Of Travel”

Nowadays, traveling is not only a favored hobby, but a necessity, too, for some people, who can probably no longer remember their life without it. But whether it’s vacation time or a business trip, they have plenty of options to choose from to get themselves from point A to point B. Even if the destination is on the other end of the world, they can get there in roughly a day, which was once a thing difficult to imagine.

Clearly, many things seemed impossible at a certain point in time; but, thanks to the development in technology and engineering, quite a few have become reality. If you’re curious to take a step back in time and see what travel looked like back in the 19-20th centuries, you’re in luck, as today we’re focusing on the period between 1830-1955.

On the list below you will find some fascinating pictures, as shared by the ‘Golden Age Of Travel 1830-1955’ Facebook group that depict everything from the first subway ride in New York, to German monorails, and much more. So wait no longer, scroll down to browse them and make sure to upvote your favorites!

#1 Baby Strollers Strapped To The Front Of The Bus In Opawa, New Zealand (1950s)

Image credits: Joyce Ward

#2 1905 Woods Electric Car

Image credits: See Twise

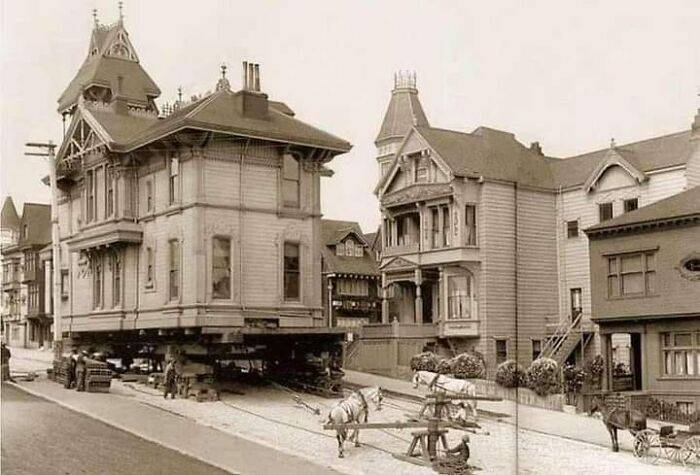

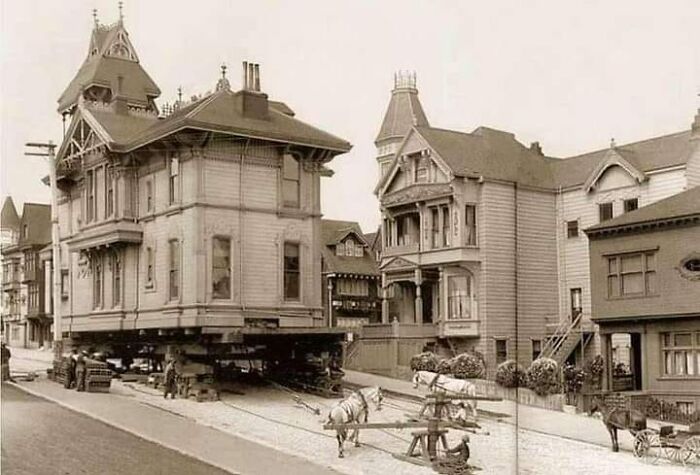

#3 A Victorian Home Being Moved Via Horse Power In San Francisco, 1908

Image credits: Ciarra Tavares-Girsback

#4 A Bicycle For The Whole Family, 1949

Image credits: Joyce Ward

#5 Alweg Monorail Train In Cologne, Germany, 1952

Image credits: The Historian's Denn

#6 London In The 1920s. A Policeman In A London Street Giving Directions To The Three Children On A Bicycle. The Bicycle Is Specially Made For Three Persons

Image credits: Endri Logos

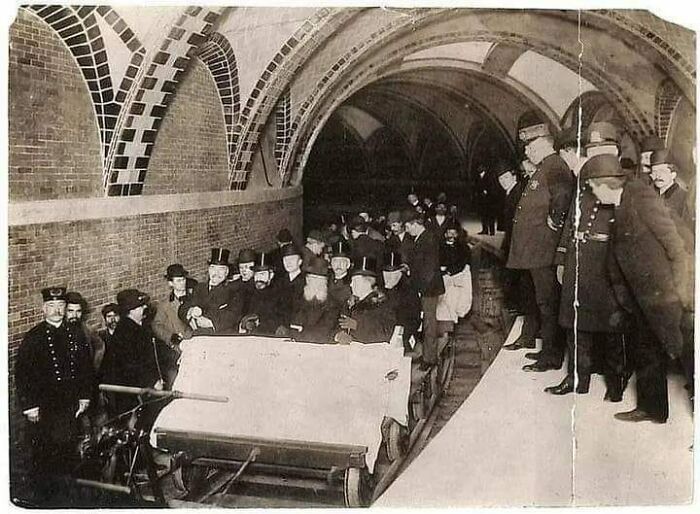

#7 The First Subway Ride In New York City History, 120 Years Ago. Original, 1904

Image credits: Hussein Saleh

#8 New York 1918 Hotel Astor Automobile Salon

Image credits: Endri Logos

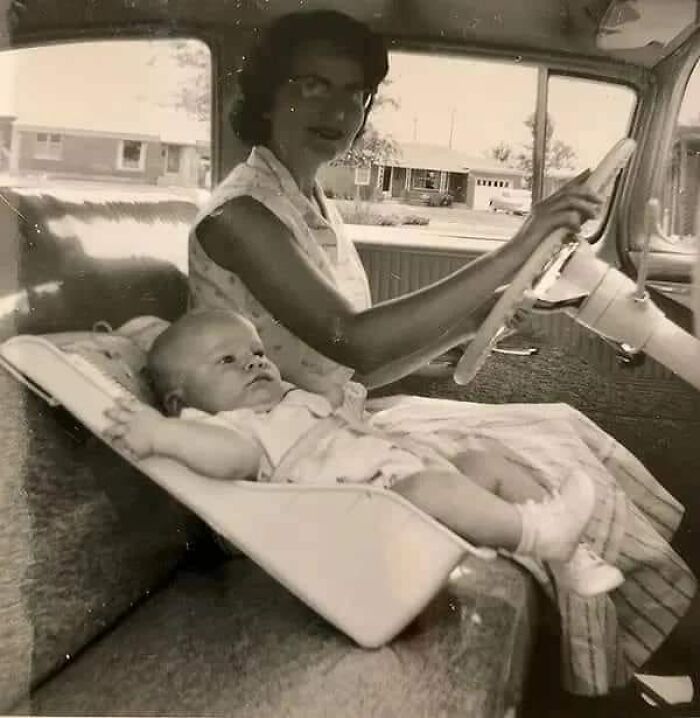

#9 Car Seats Were Not Equipped With Any Straps To Keep Baby Seat On The Seat. Instead, These Seats Depended On The Mother Extending Her Arm To Prevent The Baby From Toppling Forward. 1958

Image credits: ShutterBulky

#10 New York, USA – 1960: French Cellist Maurice Baquet Trying To Open His Car Covered With Snow During A Snow Storm

Image credits:

#11 Cycle Engineer Riding The World’s Smallest Bicycle Through The City, London, August 1937

Image credits: Royal World

#12 A Coca Cola Delivery Van In Oslo In 1938

Norway was, in addition to Australia, Austria and South Africa, one of the countries where Coca Cola was introduced in that year. (Neighboring country Sweden had to wait until 1953.) My partial colorization of Anders B. Wilse´s photo in the Norsk Folkemuseum archive

Image credits: Frank Hellsten

#13 Chief Iron Tail, Cranking An Early Automobile, 1915

Image credits: Royal World

#14 Bmw Isetta Bubble Car Custom Conversion, 1950s. And, Of Course, A Picnic Basket

Image credits: ??? ??????? ?????????

#15 Titanic Launch Into Belfast Harbour (1911)

Image credits: Ciarra Tavares-Girsback

#16 An Austin 7 Driven By B. Sparrow Loses Control At Donington Park On May 13, 1933

Image credits: Endri Logos

#17 Camp Of Scientists In The Sands Of The Karakum Desert. Turkmen Ssr, 1953

Image credits: Tomi Vaalisto

#18 Berlin, Circa 1905

Image credits: George Derenburger

#19 Passengers On Eastern Airlines In 1935

Planes were so loud back in the day that the cabin crew had to use megaphones so the passengers could hear them. Flights from the UK to Australia took 11 days. The plane could drop 100’s of feet randomly thus motion sickness bowls were placed beneath the seats.

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#20 Passengers On Board The Staten Island Ferry In 1895

Image credits: Joyce Ward

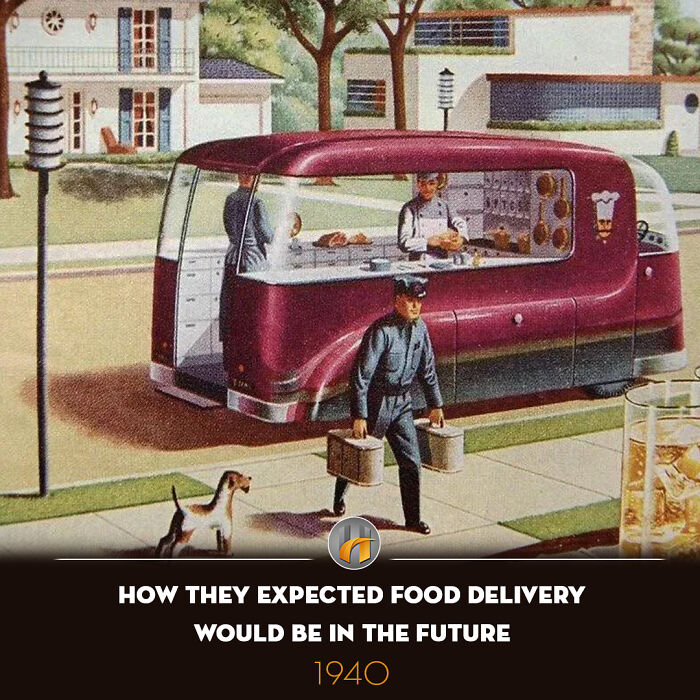

#21 Food Delivery In The Future

Image credits: Rosa Hemming

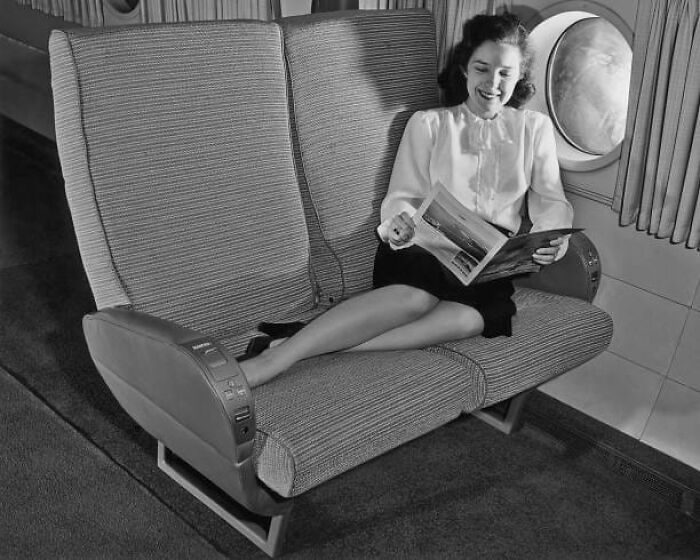

#22 A Woman Passenger Reads A Magazine On Board A Boeing Airliner, Circa 1955 Advertising

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

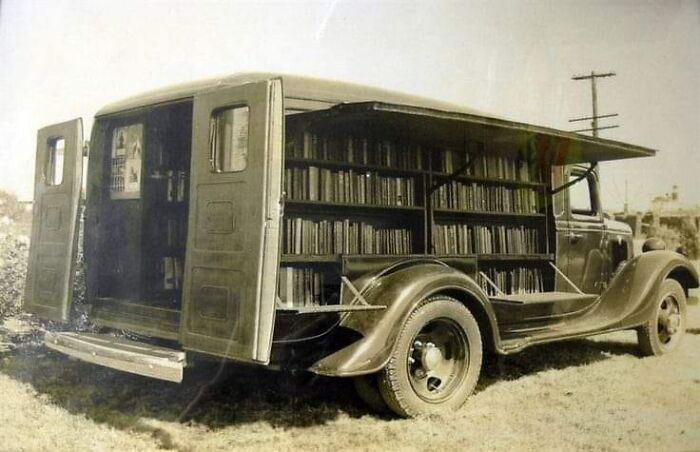

#23 Jefferson County Mobile Library, Texas’ First Mobile Library

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#24 1949 Nash Airflyte. First Sleeper Car

Image credits: Walter Hasler

#25 Firefighters Trying To Stop Fire At The Equitable Life Building During A Snowstorm, Manhattan, 1912

Image credits: Machine Lord

#26 1950s, “Flying Cars” Amusement Park Ride. The Drum Rotated And You Controlled A Brake In The Car. The Cars Would Go Completely Up And Over The Loop

Image credits: Duck & Cover, Growing Up in the Atomic Age

#27 People Waiting For The Bus. Paris 1958

Image credits: Endri Logos

#28 1931 The German Schienenzeppelin Hits Max Speed Of 120 Mph (230 Kmh)

Image credits: Kenny Callei

#29 Munich, Germany, May 1949 Of A Man And His Two Boys Riding On Their Daily Commute

Image credits:

#30 Native Americans In 1908

Image credits: Changling Mandrake

#31 Traditional Cod Fishing In Lofoten ( Nordland, Norway) In 1928

hese “åttring” boats with four (sometimes five) pairs of oars represent a continuous boat building tradition from the pre-Viking Age.

My restoration and digital hand colorization of Anders Beer Wilse´s

photo in the Norsk Folkemuseum archive.

Image credits: Frank Hellsten

#32 Henry Giulio’s Airship, The Yellow, 1903 Old Photos From The 19th Century Give Us A Glimpse Into The Achievements Of The Industrial Revolution

Image credits: Liwia Zieliński

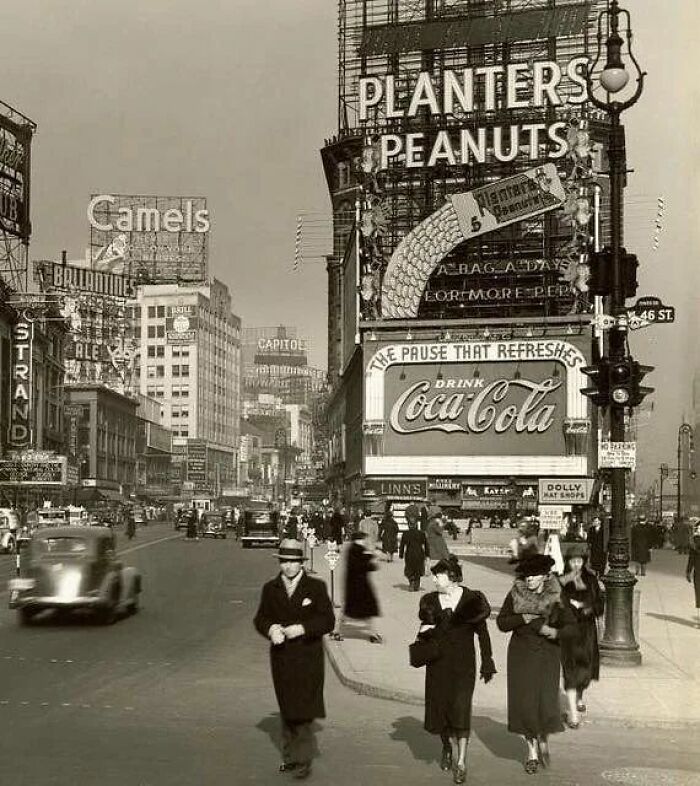

#33 Times Square, New York City 1936

Image credits: Royal World

#34 Titanic Compared To A Modern Cruise Ship

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#35 The 1938 Brazilian National Team Training On The Ship. Players Were Thin Compared To Today

Image credits: Endri Logos

#36 1951 Airline Ad By Harold Anderson

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#37 Boat Ride, 1920s

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#38 Legless Woman Poses On A Motorcycle At The Wall Of Death Motordrome C1940s

Image credits: Endri Logos

#39 Passenger Aboard An American Airliner Enroute From Washington To Los Angeles. Photograph By John Collier In 1941

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#40 Salvador Héctor Sarida, Little 6-Year-Old Motorcyclist. Buenos Aires, 1936

Image credits: Endri Logos

#41 An Amazing Capture Of Changing Times In Transportation By Photographer O. Winston Link

Image credits: Troy C. Werner

#42 A Sleeping Berth On An Imperial Airways Aircraft In 1937

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#43 A Family Getting Ready To Cruise In Their 1903 Cadillac Model A Tonneau

Image credits: ShutterBulky

#44 New York Central “Mercury” 1936

Image credits: Story Cafe

#45 Man Standing On Lap Of Colossal Figure Of Ramses, 1856

Image credits: Machine Lord

#46 A Match Day, 90 Years Ago. Tram In The Barça Field Along Carrer Anglesola (1933)

Image credits: Endri Logos

#47 Return By Bus. Buenos Aires 1942

Image credits: Endri Logos

#48 A Train Passes Through Densely Packed Housing Along Kensal Rise, London, England. March 1921

Image credits: Monique Genoud

#49 A Photograph Taken Infront Of Rome’s Colosseum, Circa 1897

Image credits: Monique Genoud

#50 Georges Tairraz II ( 1900 – 1975 ). Two Climbers Traversing The Aiguille Du Midi And Aiguille Du Plan, Chamonix, France 1932

Image credits: Gren Nation

#51 Old Train. 1940s

Image credits: ??? ??????? ?????????

#52 A Train Driver At Euston Station In London Talks To Two Young Girls On The Platform. April 1936

Image credits: ??? ??????? ?????????

#53 Maintenance Worker Painting The Sydney Harbour Bridge, Australia, 1945

Image credits: Toseef Ur Rehman

#54 1910, A Day At The Beach

Image credits: Duck & Cover, Growing Up in the Atomic Age

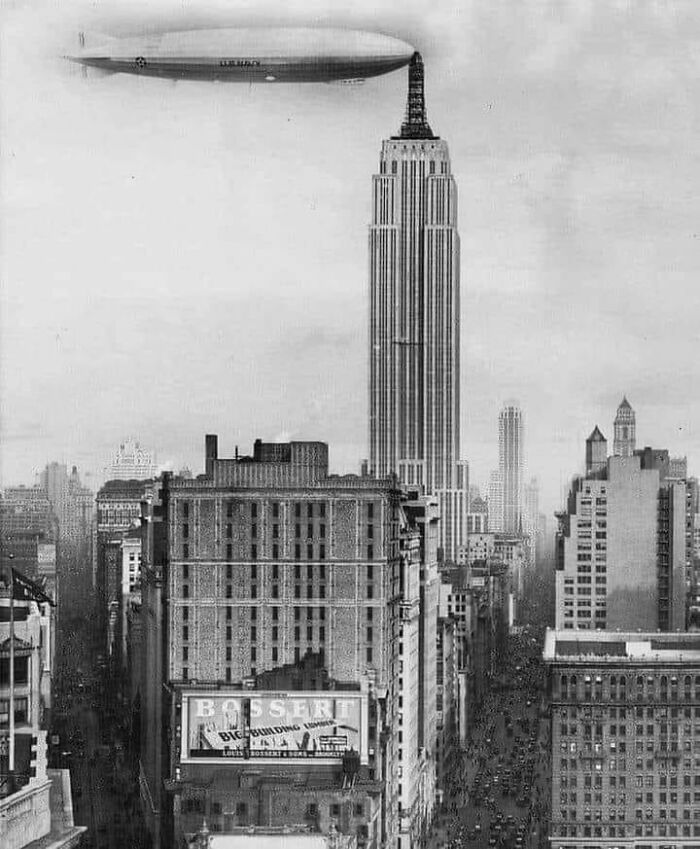

#55 The Empire State Building’s Top Was Initially Planned To Be A Docking Station For Airships In The Late 1920s

Investors believed airships would soon be used for cross-Atlantic travel, and the building’s top seemed perfect for docking.

The plan was for airships to land at the top, secure quickly, and let passengers walk into the building’s top floor. Then, they could take an elevator down to Manhattan, arriving within seven minutes of landing. A docking mast was even built on the building.

However, engineers couldn’t figure out how to safely dock an airship on a 1,250-foot building with strong winds. Airship companies considered the idea too risky, and interest waned. Still, a private blimp did dock for three minutes in September 1931, causing traffic jams below, but no unloading occurred.

The era of cross-Atlantic airships ended with the 1937 Hindenburg disaster, when the world’s largest airship caught fire while landing in New Jersey.

Image credits: Ciarra Tavares-Girsback

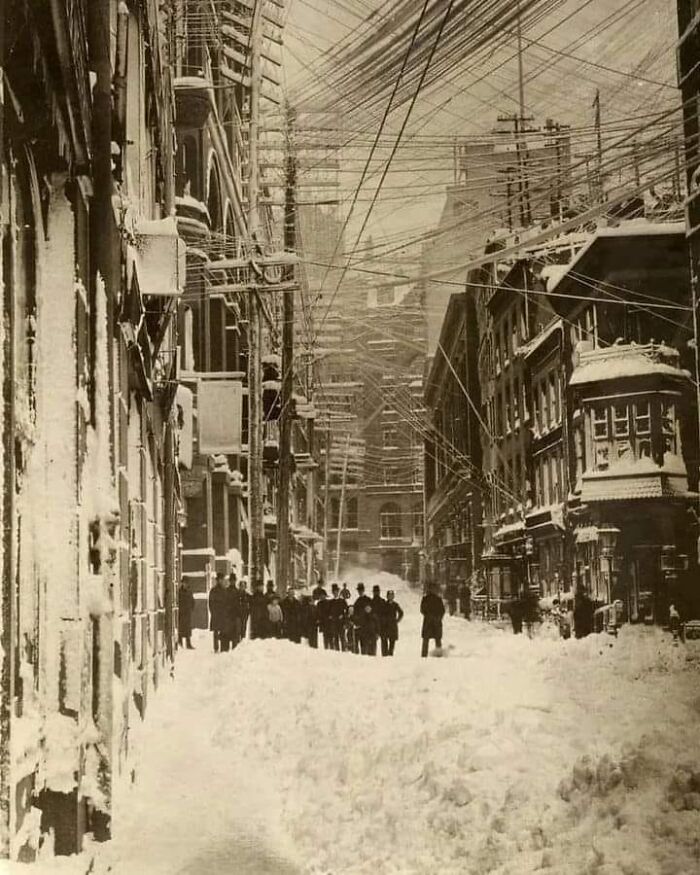

#56 New York City After A Snowstorm In 1888

Image credits: Vellore Eruthukattu

#57 Interior Of Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#58 Picnic, 1954 750 Renault

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#59 1946 Hey Mister, I Can Fix That Tire For A Coke,a Cap Gun,five Army Men And A Hula Hoop

Image credits: Craig Meador

#60 200-Year-Old Wooden Bridge In Dagestan, Built Without The Use Of A Single Nail

Image credits: Story Cafe

#61 John Cobb Set A New World Land Speed Record Of 353.30 Mph On The 15th September 1938 In The Railton Mobil Special, Becoming The First Driver To Exceed 350mph

The vehicle was powered by two supercharged Napier Lion VIID (WD) W-12 aircraft engines. These engines were the gift of Marion ‘Joe’ Carstairs, who had previously used them in her powerboat Estelle V. Coupled together, these two engines made 2,700 hp (2,013 kW) @ 3,600 rpm, and 3,939 lbft (5,341 Nm) torque.

With the huge powers thus available, the limitation was in finding a transmission and tyres that could cope. Reid Railton found a simple and ingenious solution to this by simply splitting the drive from each engine to a separate axle, giving four wheel drive.

The vehicle weighed over 3 tonnes and was 28 ft 8 in (8.74 m) long, 8 ft (2.4 m) wide and 4 ft 3 in (1.30 m) high. The front wheels were 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m) apart and the rear 3 ft 6 in (1.07 m). The National Physical Laboratory’s wind tunnel was used for testing models of the body

On 16 September 1947, the wind had picked up considerably and the course was still less than ideal, but the car was ready. Cobb decided to make a record attempt.

Setting off to the south, Cobb shifted into second gear at around 120 mph (193 km/h) and hit third at around 250 mph (402 km/h). The Railton shot through the measured mile (1.6 km) at 385.645 mph (620.635 km/h).

The tires were changed and fluids refilled. On the run north, Cobb covered the mile (1.6 km) at 403.136 mph (648.785 km/h). The two-way average of the runs was a new LSR at 394.197 mph (634.399 km/h).

And so it was that a 47-year-old man in a 10-year-old car with 20-year-old engines established a new Land Speed Record

Image credits: Leslie Marton

#62 Golden Gate Bridge Painter Walking To Work

Image credits: Craig Meador

#63 Women Fishing In A Dock, 1908. Toronto

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#64 Queensboro Bridge (Aka 59th Street Bridge) Under Construction In 1905

Image credits: Joyce Ward

#65 Daytona Beach In 1904

Image credits: Florida Memories

#66 1920s Passengers Waiting For A Thrill Of A Lifetime!

Image credits: Craig Meador

#67 1929 – Mulholland Dam Reinforced With Tons Of Dirt Shortly After The St. Francis Dam Disaster

Following the 1928 St. Francis Dam failure, the Mulholland Dam was reinforced with tons of dirt on the downstream side as a precautionary measure. Later studies confirmed that the St. Francis Dam disaster was due to geological instability, not a design flaw

Image credits: Jack Feldman

#68 1920s – The Mulholland Dam Before The Hollywood Reservoir Was Filled, With The Hollywoodland Sign Visible In The Background

Image credits: Jack Feldman

#69 Azafatas (Stewardess) De Avión, 1940s

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#70 1899 Vintage Bicycle Built For Two

Image credits: Story Cafe

#71 The Triborough Bridge In New York City In 1937

Image credits: Joyce Ward

#72 Brooklyn Bridge, New York. Then vs. Now

Image credits: Hussein Saleh

#73 Los Angeles, Bus And Two Women. 1955. By Vivian Maier

Image credits: ??? ??????? ?????????

#74 Subway Car In Manhattan In The 1950s

Image credits: Joyce Ward

#75 A Barge Maneuvering Under The Michigan Ave Bridge, Chicago In 1953

Image credits: ??? ??????? ?????????

#76 Palm Beach Airport, 1955

Image credits: Danny Fernandez Jimenez

#77 Frozen Niagara Falls, 1911

Image credits: History Defined

#78 Delta Gamma Girls Singing In A Bus Which Is Taking Them Through The Snow And Mud To The Talent Show. North Dakota, May 1950

Image credits: George Derenburger

#79 1939 Packard 8 Door

Image credits: Elisa Elena Jiménez Emán

#80 Five Female Journalists Smile As They Walk On The Airport Runway To Board A Vacation Flight After Winning The Annual ‘Prettiest Newspaperwoman’ Contest

Image credits: ??? ??????? ?????????

#81 The Greyhound Bus Company Might Have Been Founded In 1914, But It Didn’t Adopt The Greyhound Name Until 1929

Image credits: ??? ??????? ?????????

#82 Dunkin Donuts In The 1950s

Image credits: Joyce Ward

#83 1949 Brooklyn Ice Cream Truck

Image credits: Jiali Chen

#84 Wabash Ave. Chicago, 1907

Image credits: George Derenburger

#85 A Great Look At An Officer With His Indian Motorcycle In 1924, Washington D.c

Image credits: Endri Logos

Recommended Videos

2,500-Year-Old Chariot Found – Complete with Rider And Horses705 views

2,500-Year-Old Chariot Found – Complete with Rider And Horses705 views The vulturine guineafowl is the largest bird of the guineafowl family of birds.52114 views

The vulturine guineafowl is the largest bird of the guineafowl family of birds.52114 views-

Advertisements

20 Hilarious Photos Of Parenting That Will Crack You Up1160 views

20 Hilarious Photos Of Parenting That Will Crack You Up1160 views Wild Fox Become Best Friend With A Guy Who Saved Him From A Fur Farm638 views

Wild Fox Become Best Friend With A Guy Who Saved Him From A Fur Farm638 views Rare Pygmy Possums Just Got Rediscovered After Fears That Bushfires Wiped Them Out48 views

Rare Pygmy Possums Just Got Rediscovered After Fears That Bushfires Wiped Them Out48 views Shaggy Mohawk And Stunning White Plumage Flecked With Black On Back And Wings, Crested Kingfisher Is Worth Attention13 views

Shaggy Mohawk And Stunning White Plumage Flecked With Black On Back And Wings, Crested Kingfisher Is Worth Attention13 views 25 Outstanding Red Carpet Looks At The 66th Grammy Awards100 views

25 Outstanding Red Carpet Looks At The 66th Grammy Awards100 views Rare Animal Scurries Past Hidden Camera — And Scientists Are Amazed117 views

Rare Animal Scurries Past Hidden Camera — And Scientists Are Amazed117 views