The 5 Most Incredible Archaeological Discoveries Of Recent Times

The Viking disease can be due to gene variants inherited from NeanderthalsA research team led by Hugo Zeberg of the Karolinska Institute and Nobel Prize winner Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, is once again able to present new findings on the consequences of modern man’s contact with the prehistoric human species of Neanderthals 60,000 years ago.

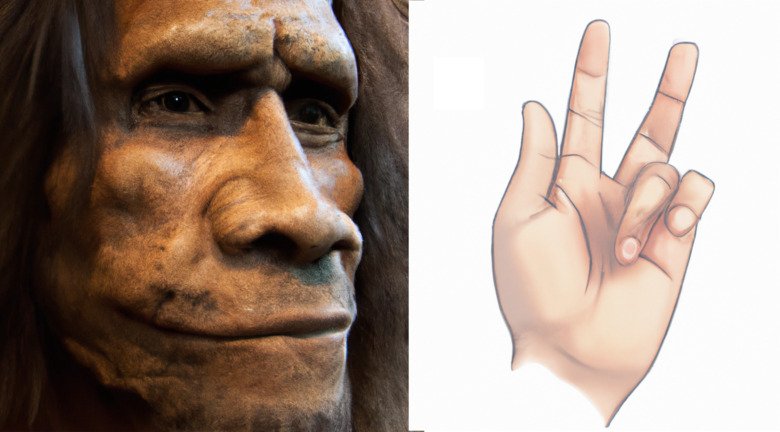

This time, the subject is Dupuytren’s contracture, which affects almost one in three men over the age of 60 in northern Europe. The disease is much more common in men than in women and often starts with a lump in the palm of the hand that grows and causes the fingers to lock in a bent position. The name ‘Viking disease’ refers to the fact that it mainly affects people in northern Europe.

Neanderthals were already established in Europe and Asia at the time when Homo sapiens left Africa and arrived there. As a result of their interaction, between 1 and 2% of the genome of humans with roots outside Africa, today originates from Neanderthals.

“Since Viking disease is rarely seen in individuals of African descent, we asked ourselves whether Neanderthal gene variants could partially explain why people outside Africa are mainly affected,” says Hugo Zeberg in a press release.

Svante Pääbo och Hugo Zeberg.

Svante Pääbo och Hugo Zeberg. Photo: Private

By comparing the genomes of nearly 8,000 people in the US, UK and Finland suffering from Viking disease with more than 600,000 healthy people, the researchers identified 61 genetic risk factors associated with the disease. Three of them are of Neanderthal inheritance, including the second and third most important risk factors.

“The study highlights how encounters with Neanderthals may result in certain diseases particularly affecting certain groups. In this case, the encounter with Neanderthals has resulted in an increased risk of developing the disease, although we must be careful not to exaggerate the link between Neanderthals and Vikings,” says Hugo Zeberg.

Svante Pääbo was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology in 2022 for mapping the genomes of extinct human species and the genetic traces they left behind.

This time, the subject is Dupuytren’s contracture, which affects almost one in three men over the age of 60 in northern Europe. The disease is much more common in men than in women and often starts with a lump in the palm of the hand that grows and causes the fingers to lock in a bent position. The name ‘Viking disease’ refers to the fact that it mainly affects people in northern Europe.

Neanderthals were already established in Europe and Asia at the time when Homo sapiens left Africa and arrived there. As a result of their interaction, between 1 and 2% of the genome of humans with roots outside Africa, today originates from Neanderthals.

“Since Viking disease is rarely seen in individuals of African descent, we asked ourselves whether Neanderthal gene variants could partially explain why people outside Africa are mainly affected,” says Hugo Zeberg in a press release.

Svante Pääbo och Hugo Zeberg.

Svante Pääbo och Hugo Zeberg. Photo: Private

By comparing the genomes of nearly 8,000 people in the US, UK and Finland suffering from Viking disease with more than 600,000 healthy people, the researchers identified 61 genetic risk factors associated with the disease. Three of them are of Neanderthal inheritance, including the second and third most important risk factors.

“The study highlights how encounters with Neanderthals may result in certain diseases particularly affecting certain groups. In this case, the encounter with Neanderthals has resulted in an increased risk of developing the disease, although we must be careful not to exaggerate the link between Neanderthals and Vikings,” says Hugo Zeberg.

Svante Pääbo was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology in 2022 for mapping the genomes of extinct human species and the genetic traces they left behind.

Advertisements

25 October 2023

Advertisements