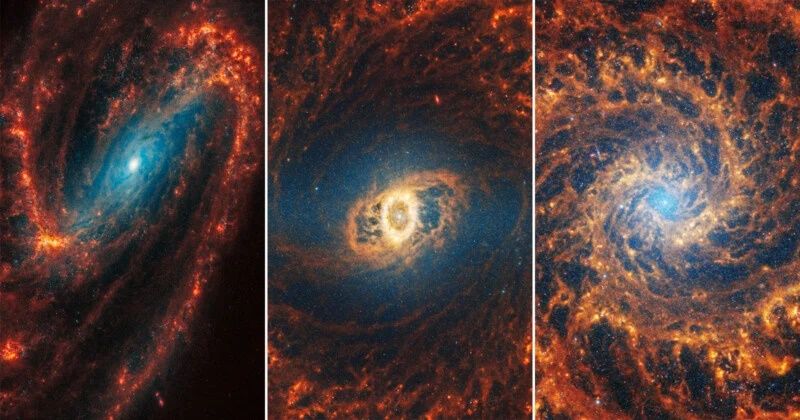

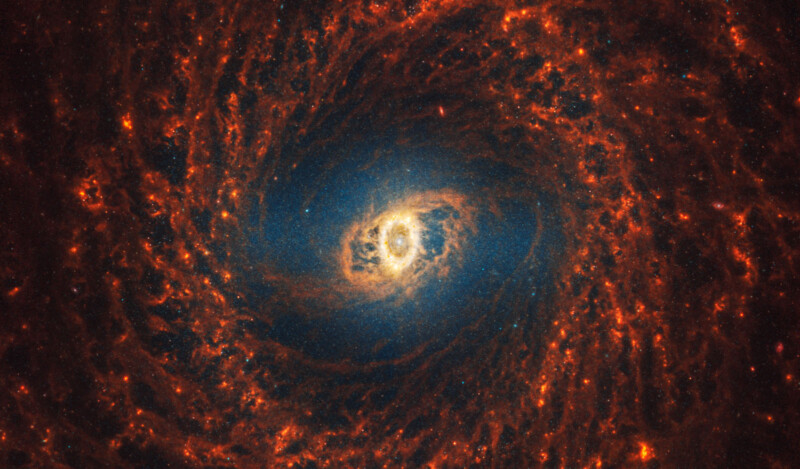

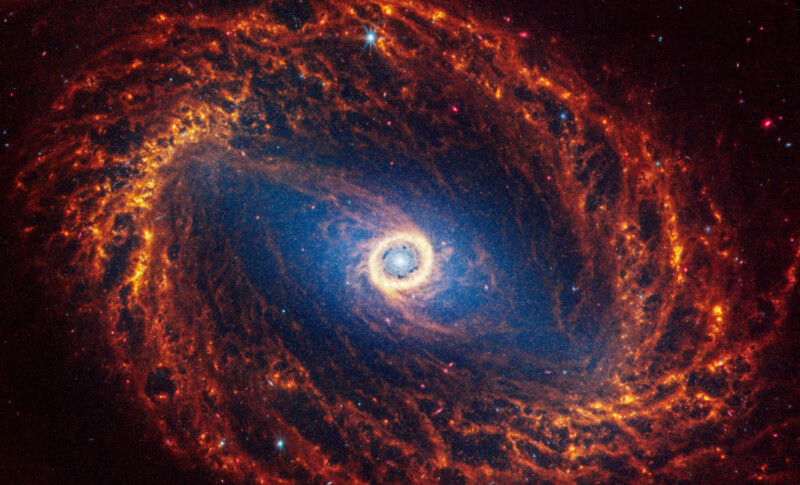

Webb Captures ‘Extraordinary’ Photos of 19 Nearby Spiral Galaxies

![]()

The James Webb Space Telescope captured images of 19 nearby spiral galaxies as part of its long-term Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS (PHANGS) program.

PHANS is supported by an international team of more than 150 astronomers. With the Hubble Space Telescope and now the James Webb Space Telescope, PHANGS is studying a sample of 74 spiral galaxies with imaging ranging from near-UV to 21 microns. The program also relies on data from the Very Large Telescope’s Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. Between these various telescopes, the PHANGS team has observation data in ultraviolet, visible, and radio light. Webb’s near- and mid-infrared cameras “have provided several new puzzle pieces,” NASA says in a press release.

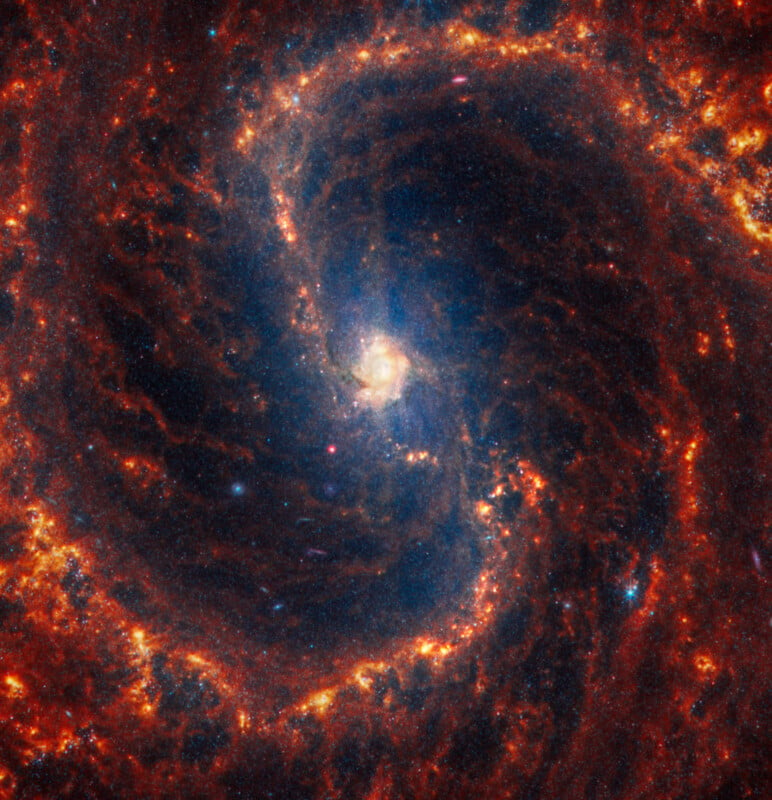

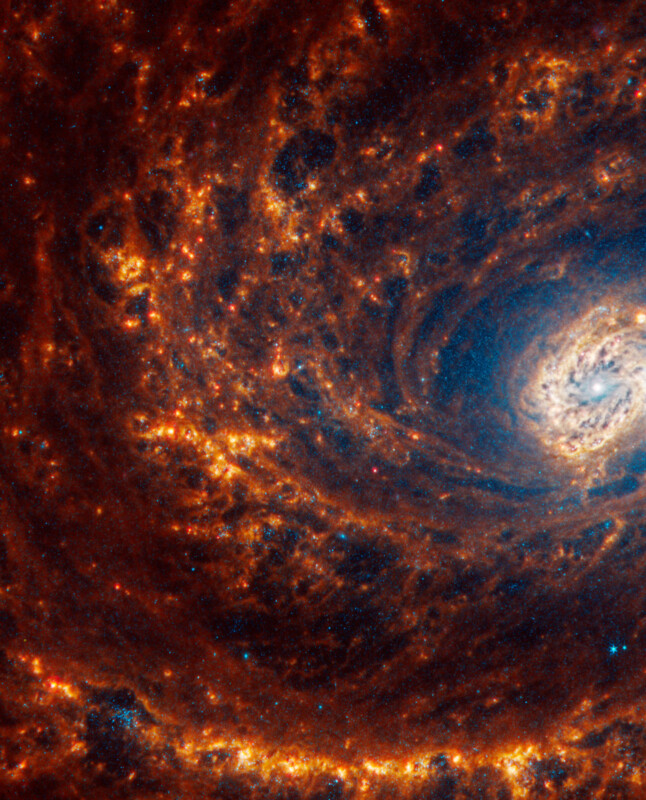

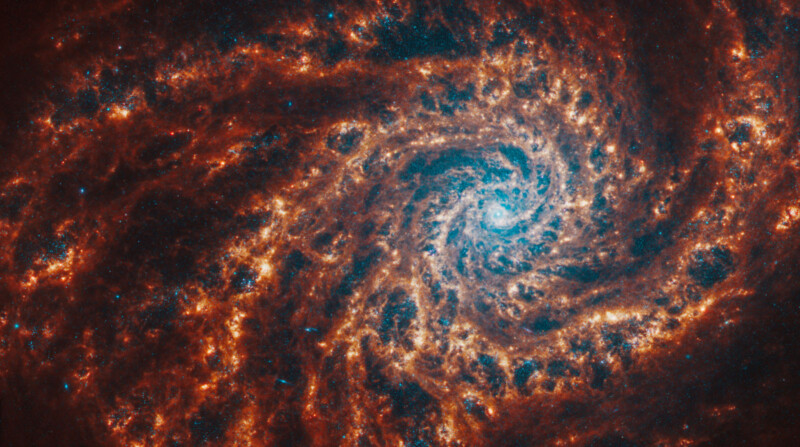

“Webb’s new images are extraordinary,” says Janice Lee, a project scientist for strategic initiatives at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. “They’re mind-blowing even for researchers who have studied these same galaxies for decades. Bubbles and filaments are resolved down to the smallest scales ever observed, and tell a story about the star formation cycle.”

![]()

One such researcher who experienced having his mind blown is Thomas Williams, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom and a member of the PHANGS collaboration.

“I feel like our team lives in a constant state of being overwhelmed — in a positive way — by the amount of detail in these images,” Williams says.

Williams led the data processing work on the new images, which took a team of 10 people about 18 months to complete.

The images may enable scientists to “fill in more of the gaps in our knowledge about the structure and evolution of galaxies, star formation, the life-cycle of stars and so much more,” Williams adds in an Oxford University news release.

Thanks to Webb’s improved resolution compared to Hubble, plus Webb’s expanded wavelength range, Webb can see millions of stars in its new images. Some of these stars appear solitary in blue tones in the 19 photos, while others appear in clusters.

“The telescope’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) data highlights glowing dust, showing us where it exists around and between stars. It also spotlights stars that haven’t yet fully formed — they are still encased in the gas and dust that feed their growth, like bright red seeds at the tips of dusty peaks,” NASA explains.

“These are where we can find the newest, most massive stars in the galaxies,” says Erik Rosolowsky, a physics professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada.

Webb has revealed many incredible details that have long been hidden from sight, including large spherical shells within the gas and dust.

“These holes may have been created by one or more stars that exploded, carving out giant holes in the interstellar material,” theorizes Adam Leroy, a professor of astronomy at the Ohio State University.

Referencing the spiral galactic arms, which lead to red and orange regions of gas, Rosolowsky adds, “These structures tend to follow the same pattern in certain parts of the galaxies. We think of these like waves, and their spacing tells us a lot about how a galaxy distributes its gas and dust.”

Current evidence suggests that galaxies grow from the inside out, meaning that star formation stars at the galactic core and then spreads along a galaxy’s arms, “spiraling away from the center.” The farther a star is from the galactic core, the more likely it is to be a younger star. Relatedly, the areas around a galaxy’s core, which appear bright blue, are typically comprised of older stars.

Some galaxy cores appear pink and red and exhibit diffraction spikes.

“That’s a clear sign that there may be an active supermassive black hole,” explains Eva Schinnerer, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany. “Or, the star clusters toward the center are so bright that they have saturated that area of the image.”

The new collection of images is a boon for the PHANGS team. Webb has uncovered an unprecedented number of stars, which are a treasure trove of data and insights for scientists.

“Stars can live for billions or trillions of years,” Leroy says. “By precisely cataloging all types of stars, we can build a more reliable, holistic view of their life cycles.”

Alongside these beautiful new images, the PHANGS team has also released its most extensive catalog to date of about 100,000 star clusters.

“The amount of analysis that can be done with these images is vastly larger than anything our team could possibly handle,” Rosolowsky explains. “We’re excited to support the community so all researchers can contribute.”

Image credits: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Janice Lee (STScI), Thomas Williams (Oxford), and the PHANGS team

Recommended Videos

Woman Lost Her Engagement Ring While Gardening Finds It Years Later Around A Carrot477 views

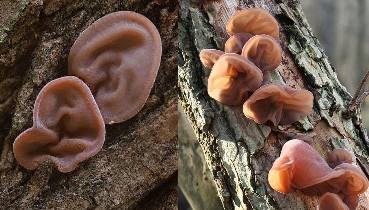

Woman Lost Her Engagement Ring While Gardening Finds It Years Later Around A Carrot477 views Oreja de Judas (Auricularia auricula-judae)490 views

Oreja de Judas (Auricularia auricula-judae)490 views-

Advertisements

2000-year-old preserved loaf of bread found in the ruins of Pompeii94 views

2000-year-old preserved loaf of bread found in the ruins of Pompeii94 views Amazing Timelapse Shows a Salamander Growing From a Single Cell Into a Complete, Complex Living Organism Over Three Weeks150 views

Amazing Timelapse Shows a Salamander Growing From a Single Cell Into a Complete, Complex Living Organism Over Three Weeks150 views New Zealand’s Amazing Moeraki Boulders Have Grown for 60 Million Years To Look Like This68 views

New Zealand’s Amazing Moeraki Boulders Have Grown for 60 Million Years To Look Like This68 views 9 of the Worst-Smelling Flowers in the World79 views

9 of the Worst-Smelling Flowers in the World79 views The elephant beetle (Megasoma elephas) is a member of the family Scarabaeidae and the subfamily Dynastinae.11038 views

The elephant beetle (Megasoma elephas) is a member of the family Scarabaeidae and the subfamily Dynastinae.11038 views 11 Amazing Examples of Insect Camouflage288 views

11 Amazing Examples of Insect Camouflage288 views

You may also like

Dutch Photographer Goes Viral With Photos Of Ground Squirrels Smelling Flowers And Here Are His 52 Best Pics

Dutch Photographer Goes Viral With Photos Of Ground Squirrels Smelling Flowers And Here Are His 52 Best Pics  Bizarre tree looks just like a real person spotted in Bulgaria

Bizarre tree looks just like a real person spotted in Bulgaria  The colorful and fragrant blooming of Muscari flowers.

The colorful and fragrant blooming of Muscari flowers.  Unique Orange and Black ‘Fox’ Poses for Friendly Photographer

Unique Orange and Black ‘Fox’ Poses for Friendly Photographer